Art needs money. Money doesn’t need art. But we need art, and it would be so very nice if art could exist without money.

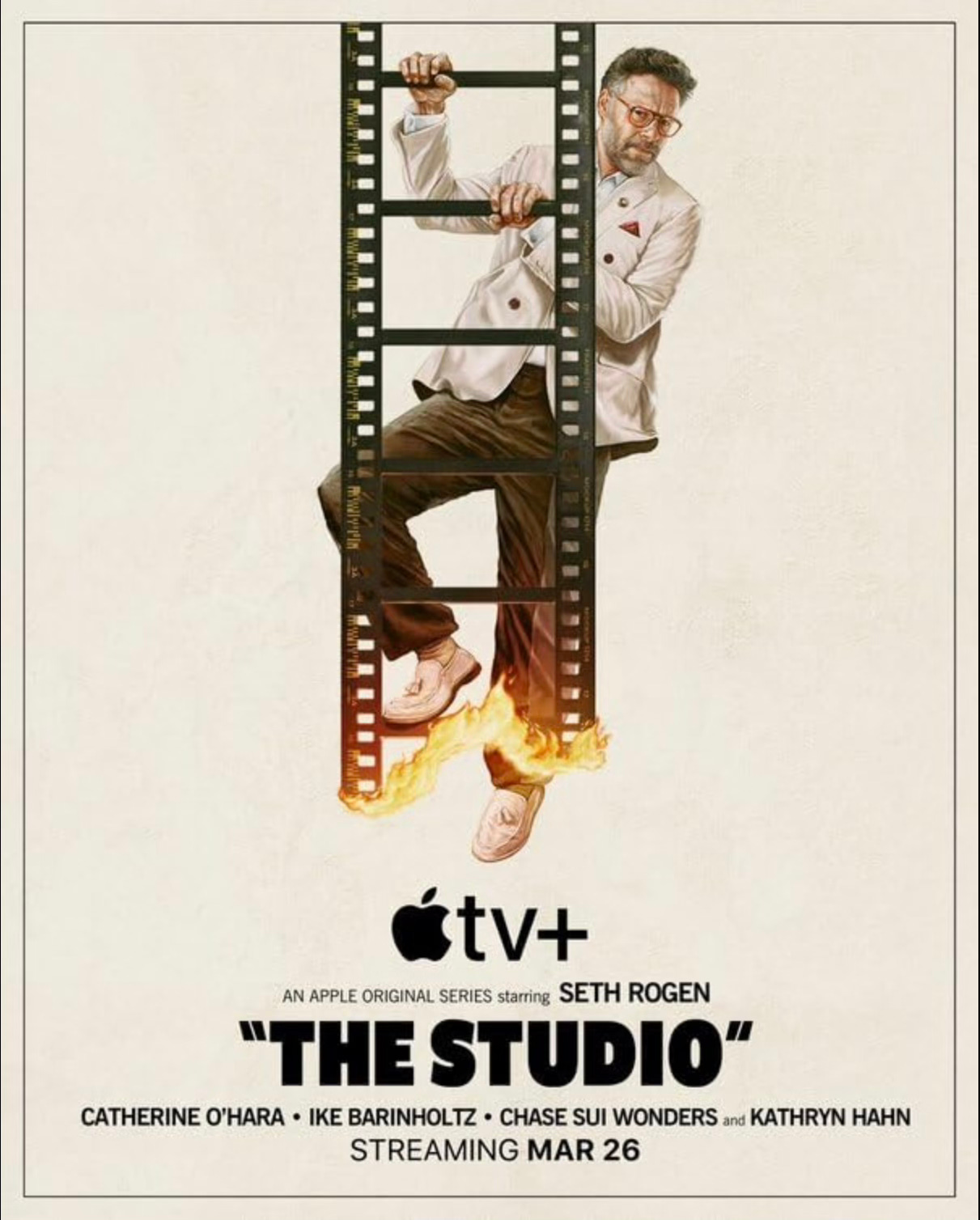

It’s frustrating, and that frustration fuels The Studio. The comedy debuted on Apple TV+ just last week and has aired three episodes so far. It’s already settled into an effective formula. Each episode features the following:

Conflict and tension between studio execs and creatives

Actors and directors playing themselves (often in self-deprecating ways)

A fictitious movie project

A standalone story

Long, cinematic tracking shots

Seth Rogen stars as Matt Remick, who has just been named the head of a major Hollywood studio. He genuinely loves film and wants to help great movies get made. But business keeps interfering.

The pilot episode, “The Promotion,” establishes a new status quo for the protagonist. Patty (Catherine O’Hara) has been fired from her position as head of the studio, so now it’s Matt’s time to lead. But Matt has his own boss to answer to—Griffin Mill (Bryan Cranston), a condescending exec who cares only about the bottom line and happily caters to the lowest common denominator.

Griffin sets a condition for the promotion: Matt needs to care about making money; he can’t squander the studio’s resources on boring artsy films that won’t sell. Though Matt yearns to support the development of brilliant movies that will stand the test of time, he says what he needs to in order to get the job. And thus, he commits to a movie about the Kool-Aid Man.

Yes, the Kool-Aid Man. A major Hollywood studio salivates over the prospect of making millions off of Kool-Aid Man nostalgia. Sadly, this premise falls within the realm of plausibility.

Matt pretends to love this soul-crushingly awful idea. But he wonders if maybe there’s some way to extract a good film out of this bland corporate IP.

Martin Scorsese (playing himself), who knows nothing about the Kool-Aid Man project, meets with Matt to pitch an ambitious film about the Jonestown cult. One of the greatest living directors wants to make a serious film about a serious and tragic situation … which, it just so happens, gave rise to the saying “drinking the Kool-Aid.”

Matt sees an opportunity to honor his commitment to Kool-Aid and help usher in a great new work of cinema directed by one of the masters of the medium. It’s obviously an ill-fated approach to a Kool-Aid movie, but he’s that desperate to make a real film and not another serving of forgettable IP-driven schlock. Can’t blame a guy for trying.

The corporate system is the enemy in the premiere, but Matt unwittingly becomes everyone’s nemesis in the second episode, “The Oner.”

It is indeed a oner—the entire 25-minute episode is shot in a single continuous take. That’s an impressive achievement, and it helps build and sustain excellent momentum.

Sarah Polley (playing herself) is directing a serious, artistic film starring Greta Lee (also playing herself). It’s the sort of movie Matt loves, and he wants to be present as they film what’s certain to become an iconic oner right before sunset. The cast and crew have a limited window in which to get this right. And then the studio head shows up and has ideas.

Problem is, he’s the studio head, so everyone wants something from him. Therefore, they can’t just ignore him or kick him out, even though he’s being a complete pest. His colleague and friend Sal (Ike Barinholtz) keeps trying to convince him to leave, and Patty keeps pressuring Sal to get Matt to leave, but everyone is being so nice to the studio head, which convinces Matt that he should stick around. It’s a perfect storm of conflicting wishes and desires threatening to drown everyone. All in one take.

The third episode, “The Note,” features another fake movie, this one directed by Ron Howard and starring Anthony Mackie. Matt and his team screen the movie as the episode opens. In addition to Sal, there’s marketing director Maya (Kathryn Hahn) and up-and-coming young exec Quinn (Chase Sui Wonders). At first, the movie seems perfect. It’s a Ron Howard film, after all, so of course it’s great. As the film reaches the climax, everyone agrees they’ve got a hit on their hands.

But then the movie keeps going—for another forty-five minutes.

Ron Howard concludes his movie with an overly artistic, self-indulgent sequence that just won’t end. And this interminable scene holds deep personal meaning for him.

Everyone is once again in agreement: Matt needs to tell legendary director and all-around nice guy Ron Howard to cut the scene that means so much to him. Matt, of course, keeps chickening out on giving the note, even though it would be in the movie’s best interests.

This time, the business decision is also the right creative decision, but it still pains the artistic soul.

Creating a good movie—whether it’s a work of art or quality entertainment—is a messy business, with so many competing forces threatening to sink the project at any point along the way. Money-hungry suits might strip it of its soul, or the artists themselves might smother it with their own excesses.

And yet we keep striving to create movies, TV shows, novels, plays, comic books, paintings, sculptures, and so much more. The process is always worth it, no matter how much chaos we need to navigate or how much corporate slop we need to circumnavigate along the way, because there’s always a chance that this might be the one.

After describing the immense frustrations of Matt’s new job, Patty tells him, “But when it all comes together, and you make a good movie, it’s good forever.”

That’s the dream. Creating something new, something that people love, something that lasts. The odds of success are always slim, often too slim, but we can’t not try.

The Studio works because it never loses sight of why people create in the first place.

Griffin Mill was the name of the protagonist character of Robert Altman's Hollywood satire "The Player".