‘Fahrenheit 451’ Is the 1950s ‘Matrix’

Brush up your Bradbury. Start quoting him now.

Non-controversial opinion: Ray Bradbury was one of the greats.

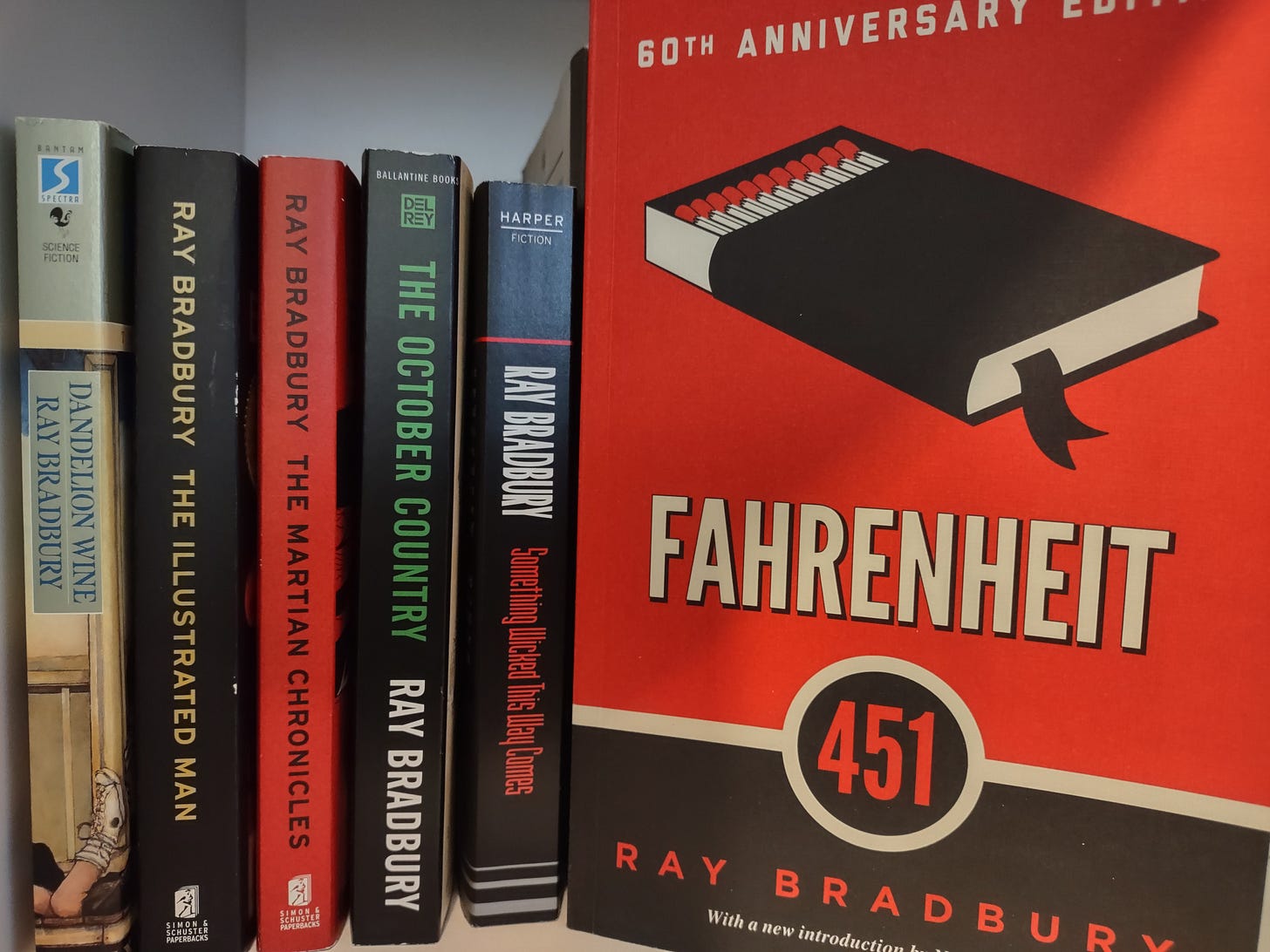

I decided to reread Fahrenheit 451 recently, so I picked up the 60th anniversary edition, which has the equivalent of DVD special features after the novel—all sorts of history and commentary about the book, including insights from Bradbury himself.

In the introduction to the 1976 audio version, Bradbury said:

“I believe in having fun first, and along the way, if you teach people, if you influence people, well and good. But I don’t want to set out to influence people. I don’t want to set out to change the world in any self-conscious way. That way leads to self-destruction; that way, you’re pontificating, and that’s dangerous and it's boring—you’re going to put people right to sleep.”

That’s exactly the right mindset. Bradbury knew what he was doing, obviously.

Fahrenheit 451 does contain a clear message, or warning—that things will not turn out well for us if we reject books and all that they hold. And yet the story remains interesting, thought-provoking, and engaging.

Bradbury’s passion for books and reading permeates the entire novel; it doesn’t merely wash over the flat surface level. He isn’t just wagging his finger and telling us that burning books is bad (which we all already know, hopefully). He’s exploring what it means to destroy ideas. He’s showing us how that scenario might play out and how it might affect us.

It’s not even just about books. Books symbolize thinking and human connection.

During the opening scene, Guy Montag meets his unusual teenage neighbor, Clarisse, and she observes, “You laugh when I haven’t been funny and you answer right off. You never stop to think what I’ve asked you.”

In this world, people have closed themselves off to curiosity. They lose themselves in a highly immersive form of television. Advertisements disrupt thought. Books are considered a public menace. People don’t even talk to each other, not in any meaningful way. Interactions are superficial. Montag’s marriage is perfunctory at best.

But Clarisse opens Montag’s mind. She simply talks to him with sincerity and genuine curiosity, sharing her unique perspective. And by listening to this new perspective, Montag’s mind starts to expand and grow hungry after a lifetime of malnourishment.

The old man Faber continues the process when he tells Montag, “It’s not the books you need, it’s some of the things that were once in books. The same things could be in the ‘parlor families’ today. The same infinite detail and awareness could be projected through the radios and televisors, but are not.”

Later, Faber says:

“The things you’re looking for, Montag, are in the world, but the only way the average chap will ever see ninety-nine percent of them is in a book. Don’t ask for guarantees. And don’t look to be saved in any one thing, person, machine, or library. Do your own bit of saving, and if you drown, at least die knowing you were headed for shore.”

The novel could easily have turned into a preachy sermon. Pull out a bunch of Faber quotes and you’ve got an excellent speech about the virtues of reading and thinking. But Bradbury avoids lecturing by carefully developing this world, creating a flawed protagonist, and respecting the antagonists enough to let them have their say, too.

Montag’s boss, Captain Beatty, represents the way of this comfortable dystopia. But Beatty is no passive participant. He’s certainly no victim. He’s an enforcer of ignorance, and he’s sharpened his own intelligence enough to cut down anyone who dares to think for themselves. The more you consider this guy, the creepier he becomes.

“Oh, you were scared silly,” said Beatty, “for I was doing a terrible thing in using the very books you clung to, to rebut you on every hand, on every point! What traitors books can be! You think they’re backing you up, and they turn on you. Others can use them, too, and there you are, lost in the middle of the moor, in a great welter of nouns and verbs and adjectives.”

Beatty uses his own cunning to try to suppress Montag’s burgeoning curiosity. He twists ideas so that they sound frightening, even menacing.

In rereading this book, I was reminded of The Matrix, in which Neo (Keanu Reeves) learns about the true nature of the world after meeting Trinity (Carrie-Anne Moss) and Morpheus (Laurence Fishburne).

Whether deliberately or not, the film’s writers/directors, the Wachowskis, followed Bradbury’s advice about having fun first. The Matrix is indeed a fun movie, full of exciting action and creative special effects. It has interesting ideas, too, but there’s no self-indulgent pontification going on. The story comes first, and the interesting ideas are baked into a science fiction tale about artificial intelligence gone rogue.

Early in the movie, Morpheus offers Neo a choice between a red pill and a blue pill. The red pill would continue to open Neo’s mind to the truth, and the blue pill would allow him to return to blissful ignorance for the remainder of his life.

(“Red pill” and “red pilled” have acquired other connotations since The Matrix. People have affixed them to political positions and perhaps even conspiracy theories in some cases. I’m not talking about any of that. This is a nonpartisan post focusing specifically on this one book and one movie. Going all in on any ideology or conspiracy theory, to the point of closing ourselves off to other possibilities, would miss the point of both works—and would make for terrible fiction.)

Let’s zero in on some of Morpheus’s lines:

Morpheus: You’re here because you know something. What you know you can’t explain, but you feel it. You've felt it your entire life, that there’s something wrong with the world. You don’t know what it is, but it’s there, like a splinter in your mind, driving you mad. It is this feeling that has brought you to me. … Like everyone else you were born into bondage. Into a prison that you cannot taste or see or touch. A prison for your mind.

The world of Fahrenheit 451 is also one huge prison for the characters’ minds, and remaining locked within is the far easier option. Montag’s wife and one of Morpheus’s crew both choose to chain themselves to ignorance and comfort. But Montag and Neo ultimately choose the more difficult path of freedom.

Instead of disconnecting from a computer simulation, Bradbury’s story suggests a different means of unplugging from the Matrix: connecting with other people, specifically other people who can absorb multiple points of view and still think for themselves.

This exchange between Faber and Montag shows the excitement both feel as Montag develops an independent thought:

“There, you’ve said an interesting thing,” laughed Faber, “without having read it!”

“Are things like that in books? But it came off the top of my mind!”

“All the better. You didn’t fancy it up for me or anyone, even yourself.”

A thinking person, like Clarisse and Faber, is the red pill that opens our minds to new possibilities and a richer view of the world. And it goes both ways—Montag also serves as a sort of red pill for Faber, who had pretty much given up until Montag arrived at his doorstep.

Book-burning “firemen,” however, are the blue pills trying to snuff out ideas. And in Fahrenheit 451, too many people accept the blue pills.

Remember Faber’s warning: “The public itself stopped reading of its own accord.”

Shameless Post

So now I’m going to encourage you to read a book by … me. Here’s the first chapter of my novel The Silver Stranger, the sequel to The Flying Woman. Thank you to everyone who’s already read it, and thank you to all who take a look now!