Superman and Self-Control

His greatest power was evident right from the start.

As I get caught up on writing the Terrific series, I’m dusting off an old post that previously appeared elsewhere, including in video form. (In the unlikely event you’re curious what I sound like, you can follow this link to watch it.)

Superman’s most super power is that he’s incorruptible. The notion that “power corrupts” does not apply to him. Thanks to a strong, wholesome upbringing, he can resist that temptation. His powers free him to do pretty much anything he wants, but he still chooses to help people. He’s the ultimate Good Samaritan, and his own free will and self-control are large parts of that equation.

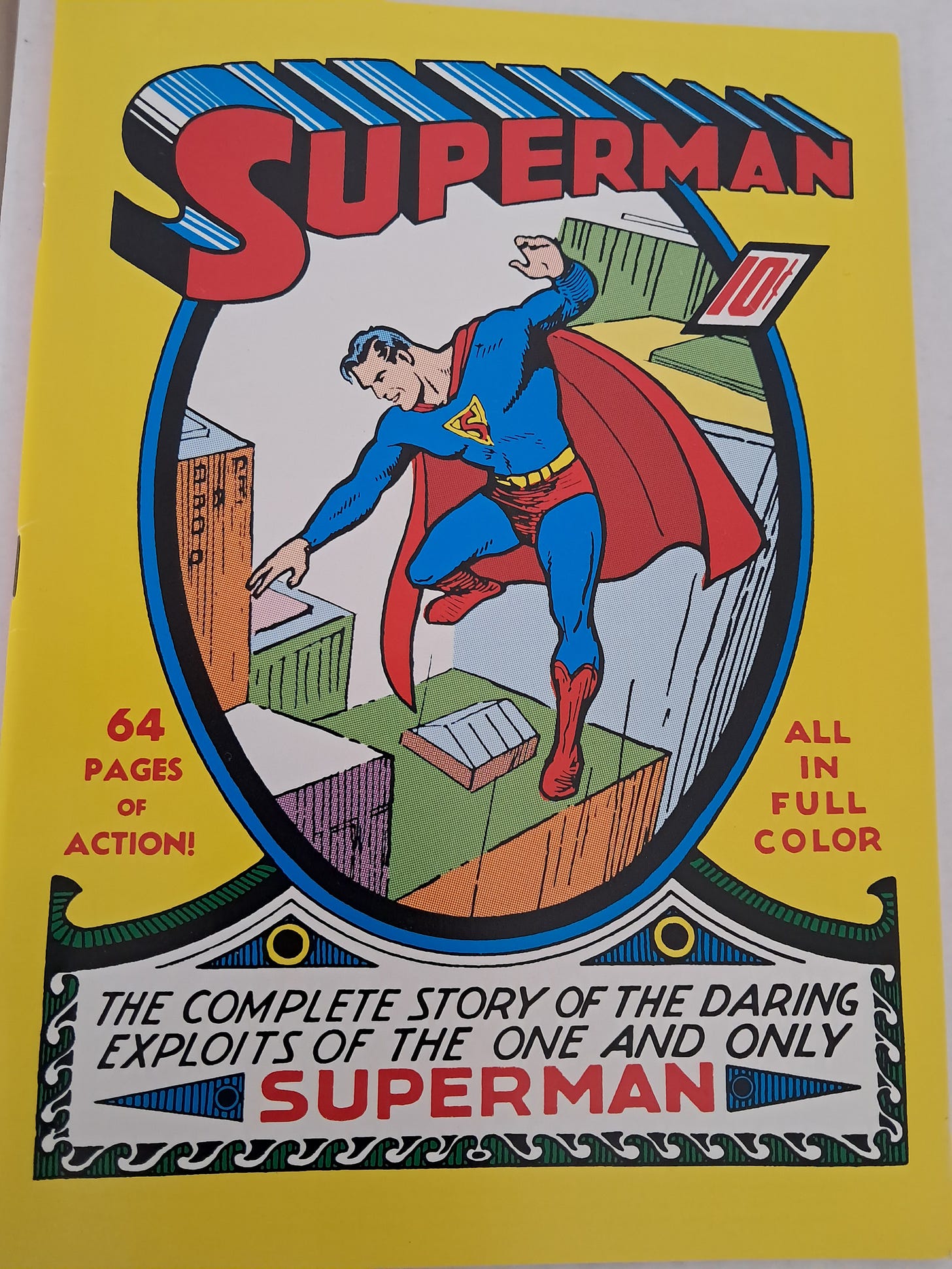

In Action Comics #1 (1938) and Superman #1 (1939), both by Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster, Superman is far from fully developed. The process of molding him into the iconic figure we all recognize had only just begun. Nevertheless, several key enduring elements are introduced early on.

I’ll focus on Superman #1, which features a more complete take on the original concept. This issue both reprints and adds to the first story from Action Comics #1. Right on the first page, an important part of his origin is laid out—his Earth parents teaching him to think of other people. He should hide his powers at first since other people might be scared, but when the time is right, he must use those powers to help anyone in need. He carries those lessons into adulthood and becomes Superman.

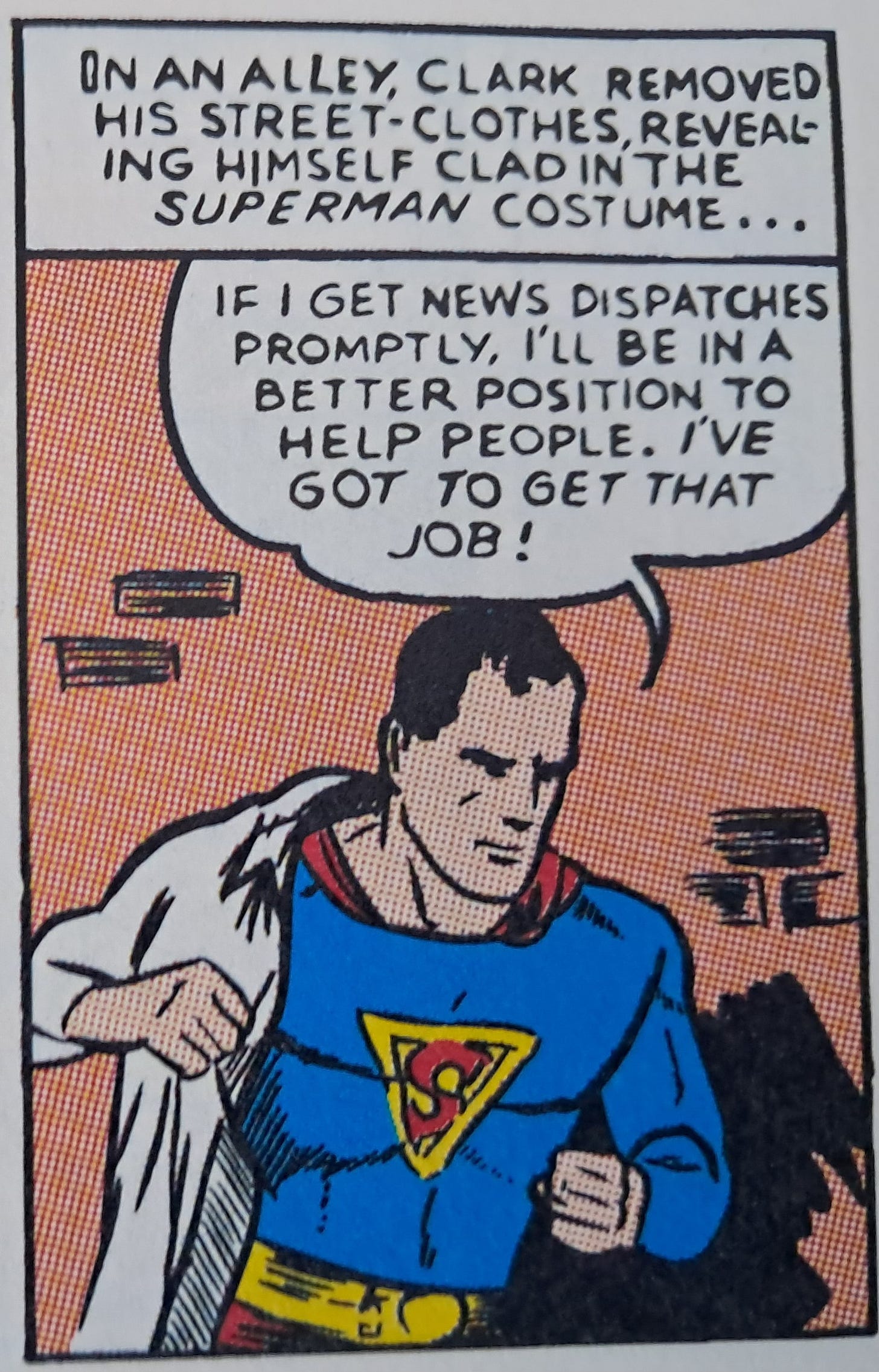

In the very episodic Superman #1, one of Clark’s first goals is getting a job at The Daily Star (not yet The Daily Planet). Even in this, he’s not thinking about personal gain; he’s thinking about positioning himself to help other people. Same with his secret identity—he voluntarily chooses to act weaker than he is so that he can help more people in the long run.

There are no supervillains in these early issues. There are just people doing bad things, and a stronger man steps in and ensures that justice is not forgotten. The first Superman exploit in this comic involves a mob rushing into a jail to lynch a man who’s already been arrested and placed behind bars. Without knowing anything about the man’s guilt or innocence, Superman leaps onto the scene—he can’t yet fly in his earliest appearances—and he demands that the mob disperse, insisting that this man’s fate “will be decided in a court of justice.”

Right from the beginning, Superman is acknowledging and reinforcing boundaries. Certain lines must not be crossed.

In this case, the arrested man indeed winds up being innocent. But even if he wasn’t, doesn’t matter—that’s not how we do things. Superman proceeds to acquire a confession from the real killer and exonerate the innocent man.

To do so, he certainly bends the law to an extent that the later, more definitive Superman might find unacceptable, but it’s still all in the service of guiding justice back onto its proper path. He’s not letting any guilty person off the hook, no matter who it is. In this case, the killer happens to be a young woman, but he’s not cutting her any slack. She tells him she’ll get the chair for this, and his response is essentially Too bad!

That attitude is certainly different from the modern Superman. But the key idea is that justice doesn’t care who you are—justice cares what you did.

In these early adventures, Superman teaches humility to the rich and powerful, or people who would like to think they’re powerful. He can be rather sneaky and manipulative in how he goes about it, and some of the specific actions would be considered out of character today.

More important, though, the early Superman targets corrupt individuals who physically harm others, whether directly or indirectly. He isn’t bullying people who simply act like jerks or express wrongheaded opinions.

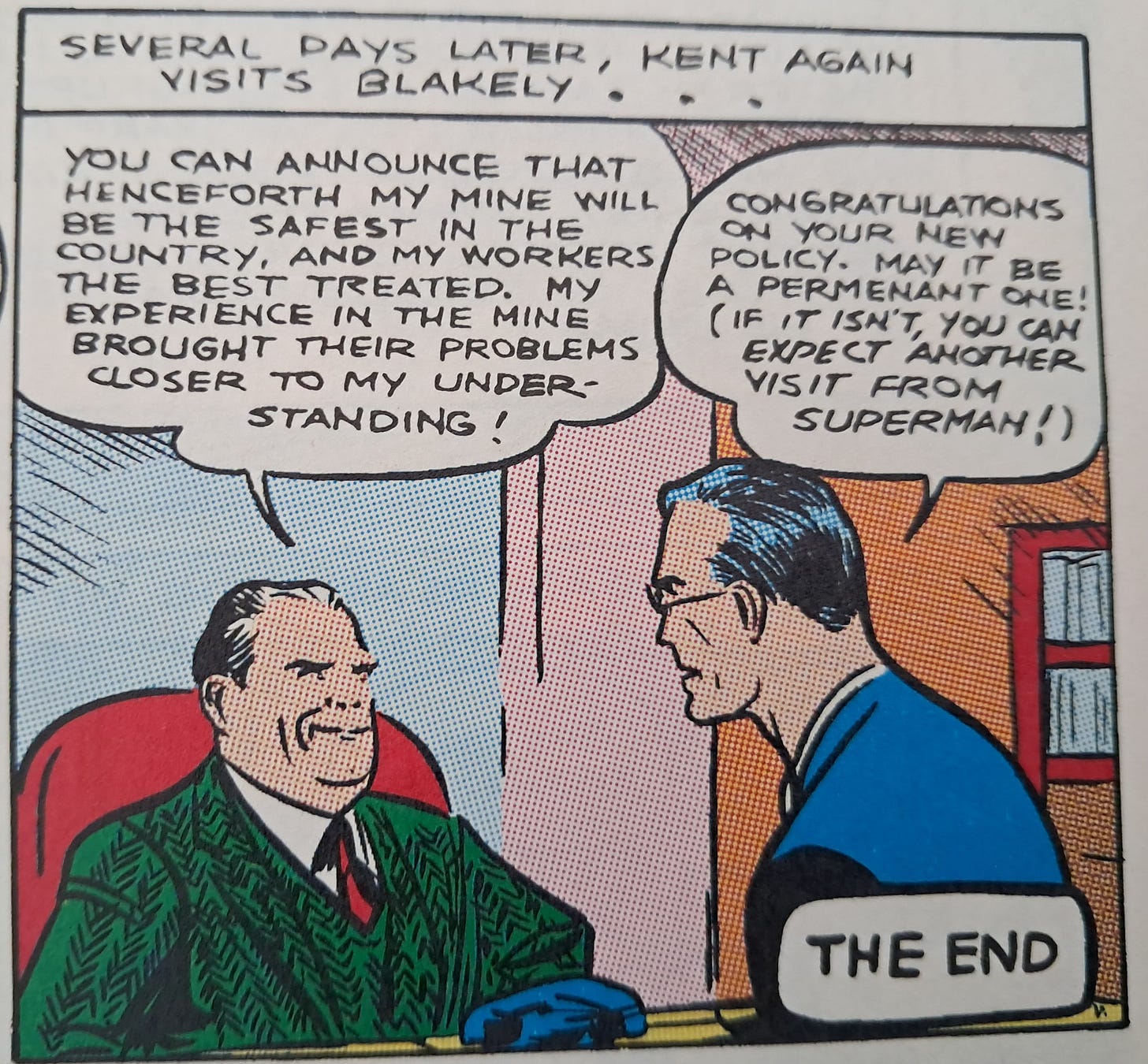

No, he restricts the role of Superman to stopping threats such as warmongers who are keeping a war going just to sell munitions and no greater purpose than that, or a man who owns a mining operation but is too cheap to ensure the safety of his workers. Superman uses the minimum force necessary, and he gives some of these people a chance to learn the error of their ways and correct their own behavior.

Superman—even the early, less powerful Superman—was certainly strong enough to impose his will on anyone he came into contact with. But he set those clear boundaries for his behavior. He serves as this juggernaut of justice who will not be stopped, and yet he’s disciplined in how he goes about it.

No one is making Superman do anything. No one can make Superman do anything. He must take responsibility for controlling himself, and that’s exactly what he does, right from the beginning.

What about Lois?

Lois Lane also debuted in Action Comics #1, and I posted about her first appearance last year. This, too, has an old video companion. (I have no plans to make any more videos, though.)

Lois Lane and the Rejection of Victimhood

As long as there’s been Superman, there’s been Lois Lane. She is the original superhero supporting character, and right from the start, she comes across as rather super herself, even without any powers. In a world where Superman is the “champion of the oppressed,” helping those who are truly unable to help themselves, Lois Lane is actively resisting opp…

And on the subject of Golden Age comics, here’s another relevant post from earlier this year:

‘Kavalier & Clay’ and the Great Escapism of Golden Age Comics

The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay is a masterpiece. The 2000 novel by Michael Chabon dives into the early days of superhero comic books and emerges as a work of genuine literature. It even won the Pulitzer Prize.

"The Daily Star" was a reference to the (still-active) most prominent newspaper in Toronto, where Joe Shuster was born. I figured it became the "Planet" to avoid possible legal difficulties.

Superman's physical and moral self-control would be a hallmark trait of many superheroes in the years to come (except for those creators who rejected it), and remains something I abide by as a superhero fiction writer.