'The Last of Us' and the Importance of a Relatable Hook

And the importance of distinguishing itself from 'The Walking Dead'

My video game tastes are stuck firmly in 1990, so I’ve never played The Last of Us and didn’t know anything about it. When the first episode of the HBO adaptation debuted, I didn’t rush to watch it and wasn’t sure I ever would. But then people kept raving about it, so I got curious.

Good word of mouth can get me to turn on a show, but the show itself still needs to win me over. And unlike, say, a Marvel show, this one couldn’t count on any preexisting affection to extend my patience if it didn’t grab me during that first episode.

The Last of Us starts with an interesting idea—that rising temperatures could allow fungus to infect people and turn them into a weird type of zombies. An interesting idea, however, does not guarantee a good story.

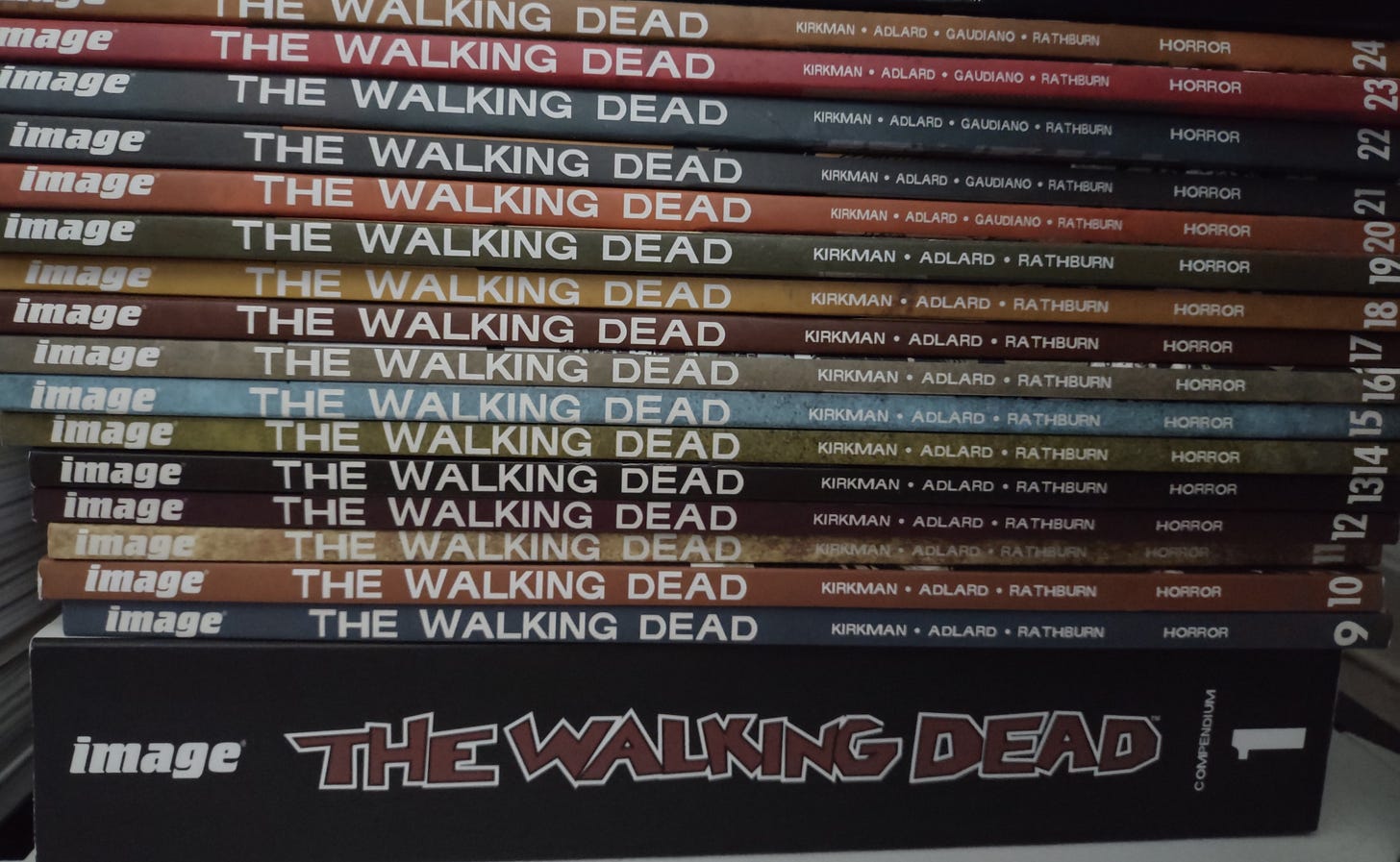

If this interesting idea merely set up a routine zombie apocalypse scenario, I’d have no reason to keep watching. I’ve already seen zombie apocalypses. The Walking Dead wore me out on zombie apocalypses. Even though both the comics and the TV show started off strong, I’ve yet to finish either version. After twenty-four trade paperbacks and just over six seasons, I wasn’t entering another zombie apocalypse lightly.

The Last of Us needed to distinguish itself early on. And it did.

(I don’t think I’m spoiling much beyond the premise, but proceed at your own risk.)

This show isn’t about mere survival. It’s not about trying to carve out a barely decent life in a world that’s already ended. It’s not about who will die next. Based on the few episodes that have aired, The Last of Us is about the importance of each individual life, and it’s fueled by the belief that as bad as things have gotten, there’s a chance, however slight, that we might be able to turn things around.

The pilot episode shows us the world falling apart about twenty years ago. And it works wonderfully because the show zeroes in on one single dad and his teenage daughter. Their relationship grounds everything. Joel (Pedro Pascal) isn’t just trying to save himself—he’s trying to save his kid. If you have a child in your life, you can relate to that. A guy trying to survive can be tense and suspenseful, but when that guy also needs to ensure his child’s survival, the stakes rise exponentially.

After the show skips ahead to 2023, Joel is tasked with protecting another teenage girl (Ellie, played by Bella Ramsey). And this girl potentially holds the key to curing the pandemic that’s ripped the world apart. This zombie apocalypse might be fixed because of the efforts of a few, and that’s far more interesting than mere survival or the question of Who will die this week?

And Joel is not perfect, which is also key. He’s carrying some old wounds that will likely create friction as the series progresses. He’s got things to work on. By contrast, Ellie was born into this post-apocalyptic world, so the everyday relics of the old world awe her. Even an old clunker of a car acquires a sense of grandeur. Her perspective, her fascination with the (formerly) mundane, adds a lot of charm to the mix.

Part of what burned me out on The Walking Dead was the lack of a clear end goal. Yes, it started off in the right place—Rick wanted to find and protect his family. Plus, the early comics had masterful tension and suspense. Despite some clunky dialogue, they were page-turners. But then both the comics and the show descended into nihilism as the characters did what they needed to in order to survive.

It’s right there in the title.

The main characters kept searching for a place to settle down, but something always went wrong, propelling them into another search for another new home. And the zombies were here to stay. There seemed to be little hope of ever rebuilding civilization. Things might get slightly better, but that was the best they could hope for.

New characters increasingly felt disposable, as though the scripts were fattening up their development only just enough before slaughtering them for zombie consumption. And tension inevitably fades. Worse, the season six finale was anti-tension—we knew someone was just killed, but we had to wait until the season seven premiere to find out who, at which point the urgency had evaporated, as did my interest in The Walking Dead. (However, if the comic or show became amazing after I dropped off, please let me know!)

Even though the fate of the world is at stake in The Last of Us, we (so far) perceive it through the lens of just a few lives at a time. Often, protecting a single life proves more compelling than saving the entire world. We can get to know a single character. We can care about what happens to that individual specifically. Though important, the entire world is more of an abstract concept, especially in the context of fiction. The further out we zoom, the more details we lose. And good storytelling hinges on the details. We need specificity to anchor ourselves.

It’s possible that The Last of Us will crash and burn, or it might meander and go nowhere. Always a risk. But I’m on board for at least the first season—not for the fungus zombies or carnage or dystopia, but to watch this one man protect this one kid and potentially help countless other people in doing so.

This Is the Way

I’m reminded of the other show in which Pedro Pascal shepherds a kid through dangerous territory: The Mandalorian.

The first time I turned it on, I stopped after ten minutes, thinking, I don’t care about this bounty hunter stuff. But then I gave it another shot and saw the pilot through to the end. Once Baby Yoda was introduced, everything clicked: Oh, this about protecting a child. I get it now. And I’ve been watching since (though I suspect it has only one more good season before it starts becoming stale).

The next Star Wars show, The Book of Boba Fett, was missing a hook like this, and I gave up after two episodes. Boba Fett, Tusken Raiders, and Tatooine politics were not enough to sustain my interest. The only reason I went back and finished the season was because they slipped in a couple of bonus Mandalorian episodes.

Cool ideas, interesting world-building, big action set pieces—that’s all well and good, but specific characters with relatable motives give us a reason to care.