I read plenty of superheroes and plenty of history, so I especially enjoy superhero history. Golden Age comics are fascinating specifically for their historical value.

Though the characters have endured, the original 1930s and 1940s comics would not have endured on their own merits. They were created as pulpy, disposable adventure stories for boys. To the modern adult reader, the main appeal is exploring the roots of the superhero genre and seeing these characters stripped down to their foundation.

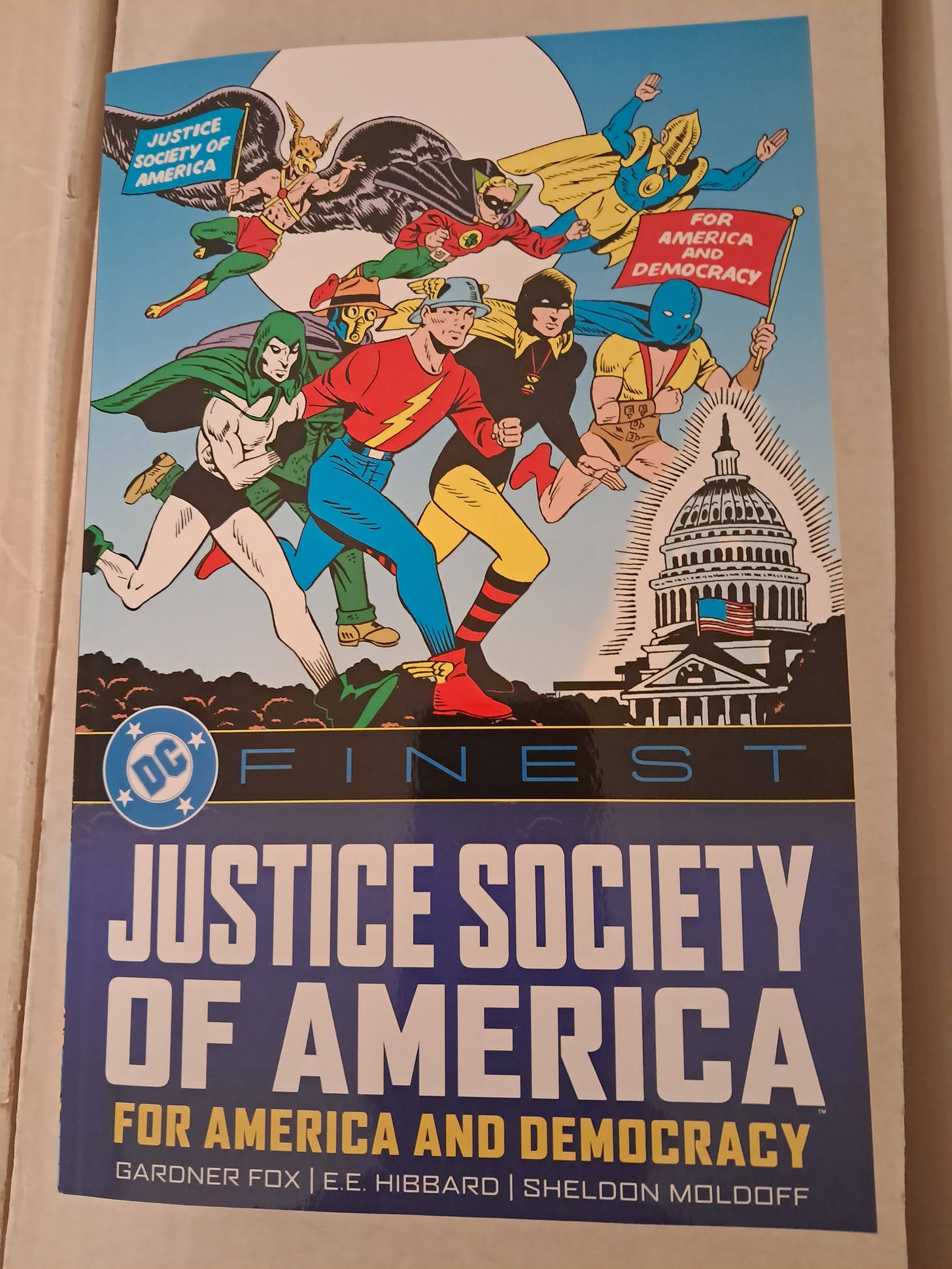

That’s why I picked up the DC Finest collection Justice Society of America: For America and Democracy. The 605-page volume reprints stories from All-Star Comics #3-12, which came out in 1940-42. Yes, 10 issues take up 600+ pages. You got a lot for your dime back then.

Gardner Fox wrote the bulk of these issues, and a battalion of artists drew them. The collection gives primary billing to E.E. Hibbard and Sheldon Moldoff, but many other names appear in the interior credits.

(Be warned, though, that even though Wonder Woman debuted in All-Star Comics #8, that story is not included in this collection because it’s not related to the Justice Society at all.)

All-Star Comics #3 introduces the Justice Society of America—the first gathering of the world’s first superhero team. And it’s basically just a social gathering. The members sit around a table and swap stories of their greatest exploits. All-Star Comics is an anthology series in disguise, and the Justice Society serves as the framing device.

It’s a great way to sample a variety of early superheroes. The original roster consists of the original versions of Flash, Green Lantern, Hawkman, Doctor Fate, Sandman, Spectre, Hourman, and Atom, with junior member Johnny Thunder. Each member gets a solo adventure in five to seven pages (though Johnny Thunder merely gets a two-page prose story), and each adventure concludes with a brief note advertising the hero’s usual title. “Follow the SPECTRE’S exploits each month in MORE FUN COMICS!”

In later issues, the members break off into separate adventures while working toward a common goal, but the first issue gives us stand-alone solo tales that represent the various JSA members in their natural element.

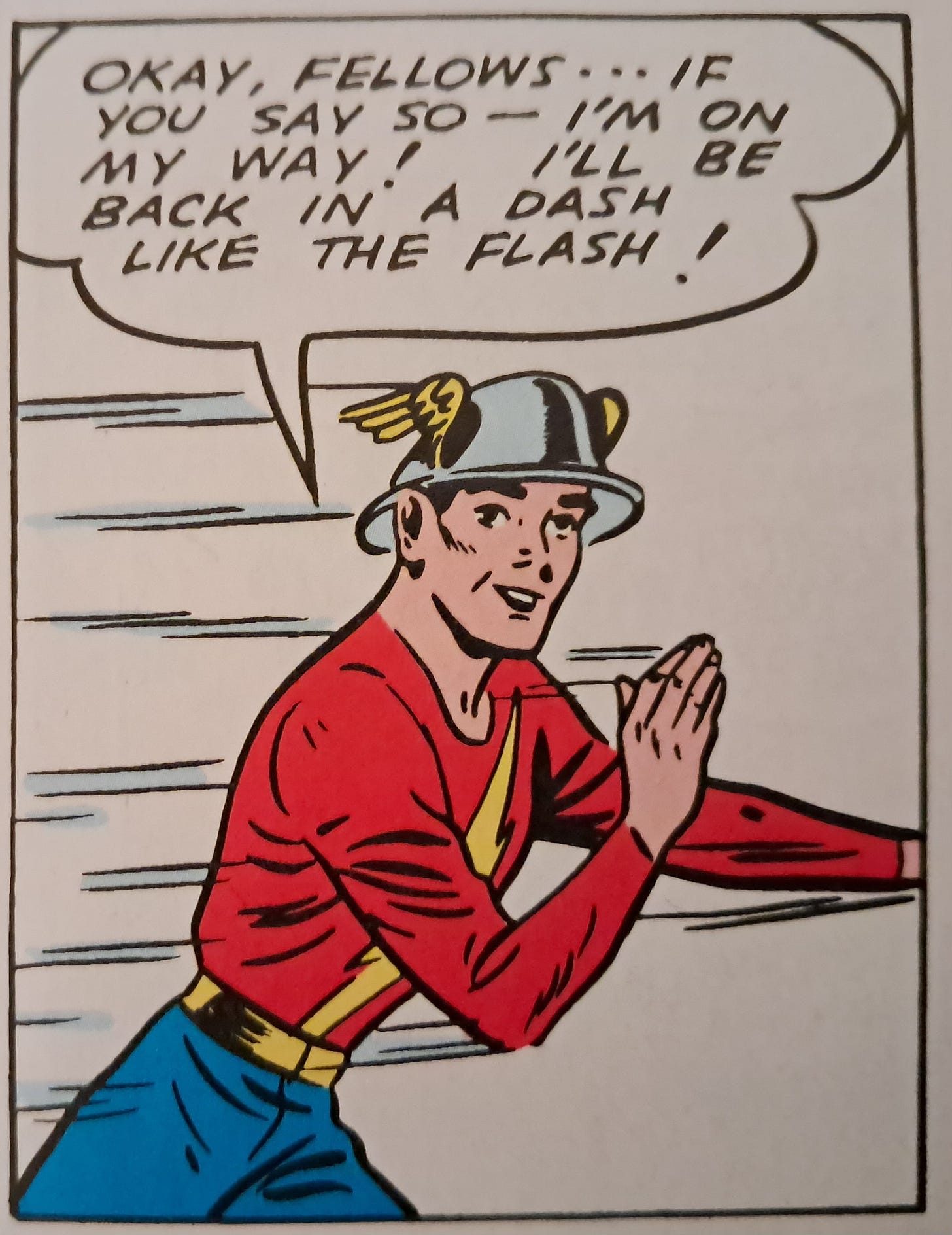

Each character possesses a distinct visual flair. The Flash is always zipping around the panels in bright red and blue. Green Lantern glows. Doctor Fate exudes magic while the Spectre gets surreal. The Sandman combines a cape, gas mask, and suit and tie, resulting in a memorably strange appearance that’s also down to earth, but the Hawkman soars high above the earth with his almost bare chest and wide, lush wings.

The art is where the book shines. Golden Age artwork isn’t nearly as refined as later eras of comics, but there’s a special elegance in the simplicity. Young artists spilled raw creativity and imagination all over these pages.

It's not hard to tell these gentlemen apart at a glance. But if you were just listening to the dialogue, you’d understandably mistake them all for the same man. The only one who sounds distinct is Johnny Thunder, and that’s because he’s the annoying sidekick-type character and not the brightest of bulbs.

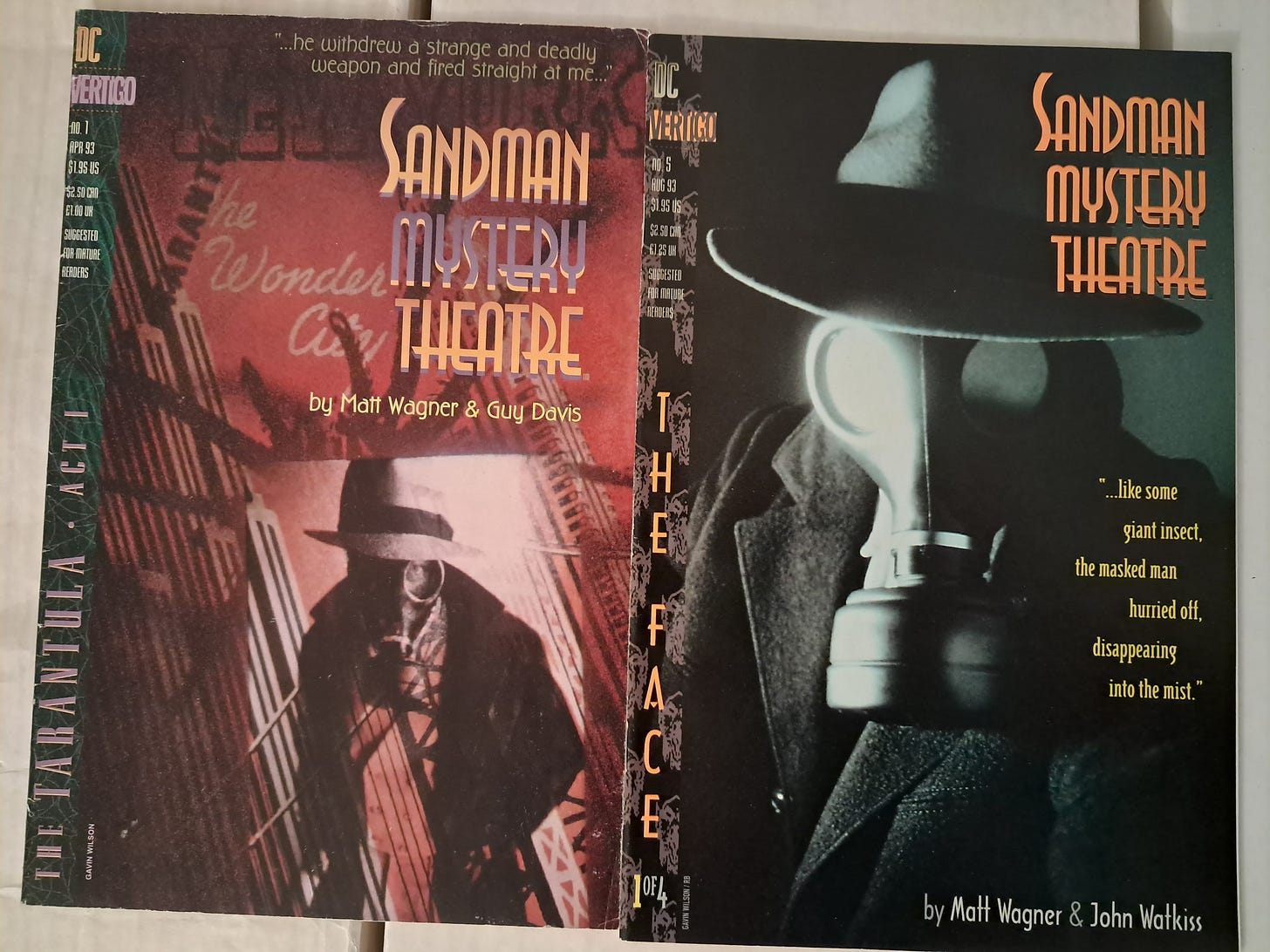

These stories are all plot and no character development, but they can serve as wonderful creative stimulants. The Justice Society members are colorful blank slates, and the memorable imagery makes me want to fill in those blanks. The 1990s Vertigo series Sandman Mystery Theatre did just that, fleshing out Wesley Dodds and romantic interest Dian Belmont into actual characters in adults-only noir-inspired stories.

Interestingly, a few girlfriend characters know the hero’s secret identity in these 1940s books. Flash, Sandman, Doctor Fate, and Hawkman are all open and honest with their significant others. Hawkman even gives his lady friend a pair of wings so she, too, can fly.

Shiera Sanders becomes Hawkgirl for the first time in #5, initially to serve as a decoy for Hawkman. She’s not a JSA member, but she’s a regular in the Hawkman chapters. We meet her as a wingless civilian first, one who might be even more brazen than Lois Lane.

In #4, Shiera is annoyed that she’s been left out of the Justice Society meeting, so she decides to vacation in Hollywood. However, while riding in an airplane, she spots Hawkman across the sky, so she grabs a parachute and jumps out of the plane.

Yes, she exits the plane that is flying through the sky. Of course, the chute fails. Fortunately, Hawkman happens to notice her in time. That’s one way to get your wings.

Decades later, Hawkgirl became one of the best characters in the Justice League animates series, so it’s interesting to see this early and very different version of her. In #11, she and future Justice League teammate Wonder Woman meet in their civilian identities.

Diana notices that Shiera is awfully friendly to both Carter Hall and Hawkman, so she gets suspicious. “Shiera must be a two-timer! She’s glad to see Hawkman and she was mooning about Carter Hall!” Early Wonder Woman rushes to judgment, it seems.

Justice Society membership included some meta criteria. Once a superhero graduates into his own solo series, he becomes an honorary member and no longer participates in Justice Society missions. Superman and Batman are the original honorary members, and Flash soon joins their ranks, followed shortly later by Green Lantern.

Flash and Green Lantern receive friendly send-offs. However, Hourman—who did not earn his own title—merely disappears between issues, never to be spoken of again. We can read between the panels and infer that the fellows discovered Hourman’s reliance on popping pills to acquire his powers, so they staged an intervention. Either that or the character was less popular, so he got quietly sidelined. You decide!

In a later issue, the group names a special associate member: J. Edgar Hoover. He’s never identified as Hoover, and his face is always obscured, but the team meets the “F.B.I. chief” in a couple of issues. And, well, America had only one of those in this era.

“And, incidentally—he’s one swell guy!” Flash tells the team at the end of the first issue.

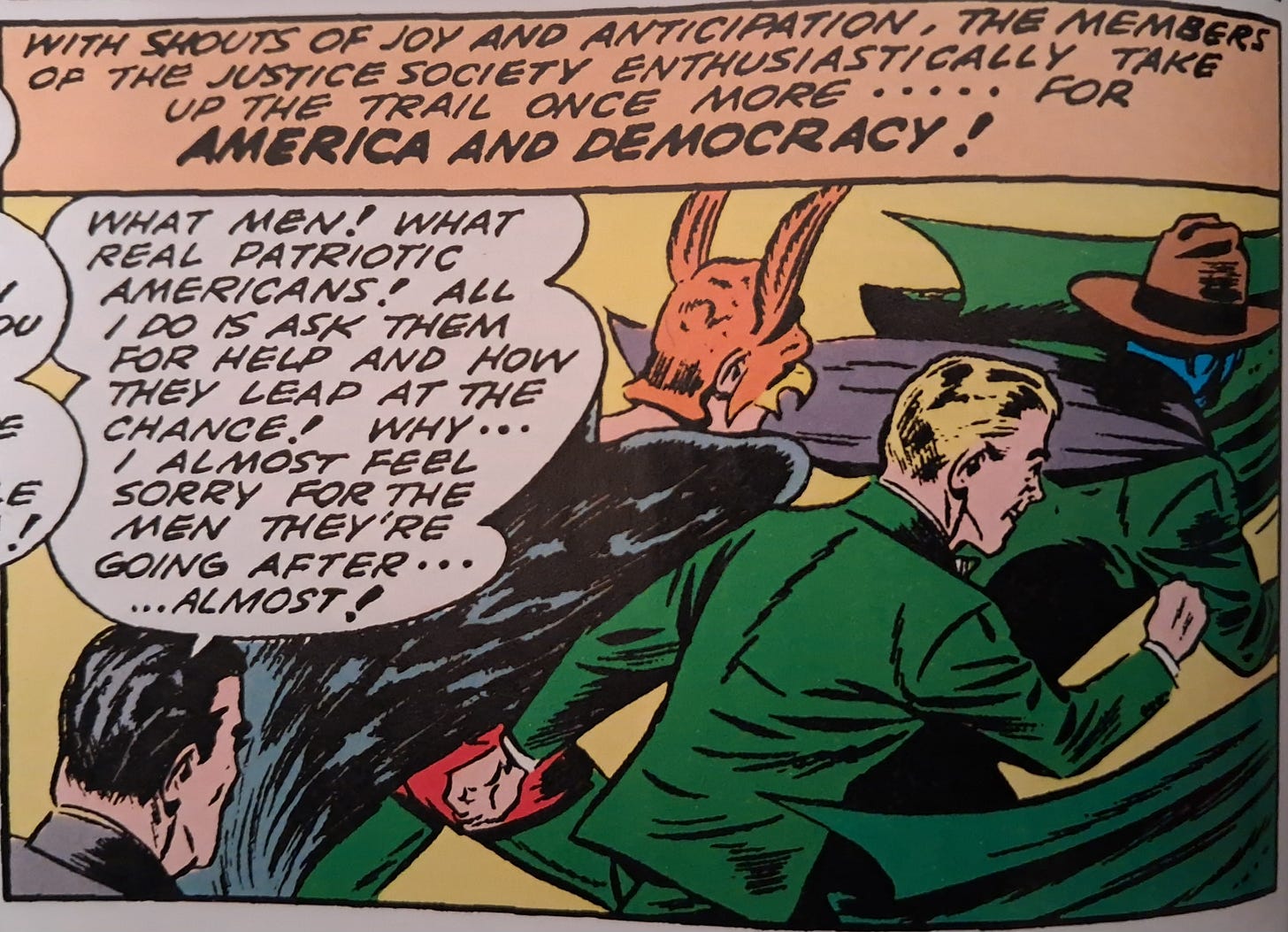

Hoover sends the team on missions, and they’re always happy to do their part for America and democracy—so much so that this becomes a battle cry.

Some of these books double as wartime propaganda. And while opposing the Axis powers was certainly the correct position to take, they sure aren’t subtle about it.

After Pearl Harbor, most of the members even decide to join the Army—except the Spectre. Lest anyone accuse him of avoiding service, the Spectre accurately points out that ghosts cannot enlist.

The propaganda takes a racist turn in the later issues. The depictions of Japanese soldiers would not pass muster today and should not. At one point, Atom even disguises himself as a Japanese man, and yeah, it’s not good. But present-day DC made the right call in not censoring those parts. The main interest here is the historical record of early comics, and you can’t change the historical record.

These early stories are relatively grounded compared to later eras of comics. The heroes face off against crooks, spies, saboteurs, mad scientists, and the like but no real supervillains. The most outlandish story sends the team 500 years into the future (but still in separate adventures in the future). The issue foreshadows some of the Silver Age zaniness to come, but even this is fairly tame. This collection is devoid of alien invasions, alternate realities, and cosmic stakes. There was simply no need.

A man with wings. A crimefighter in a gas mask. A speedster with a big lightning bolt on his bright red shirt. This was all exotic and new in the early 1940s and all inherently exciting.

The Justice Society left plenty of room for further innovation. What if superheroes had … now bear with me here … what if they had distinct personalities?

But this team once was the innovation, and the individual members, along with Superman, Batman, and others, were the innovation just shortly before. The Golden Age writers and artists set up the canvas and splashed thrilling colors all over it, inspiring generations of future writers and artists to keep filling in all those wonderful blanks.

Loved the look into this collection and the early days of the JSA!

As you pointed out, it's pretty cool that even though the early stories were created as "disposable" (literally, in some sense, since a lot of comics got recycled during wartime), a lot of the characters managed to endure and be an inspiration for future creators and stories!

-"Just watch me, honey." Canadian Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau must have read this issue in his youth, because his use of "just watch me" as a response to a question to his invoking of the War Measures Act was a major turning point in the October Crisis of 1970.

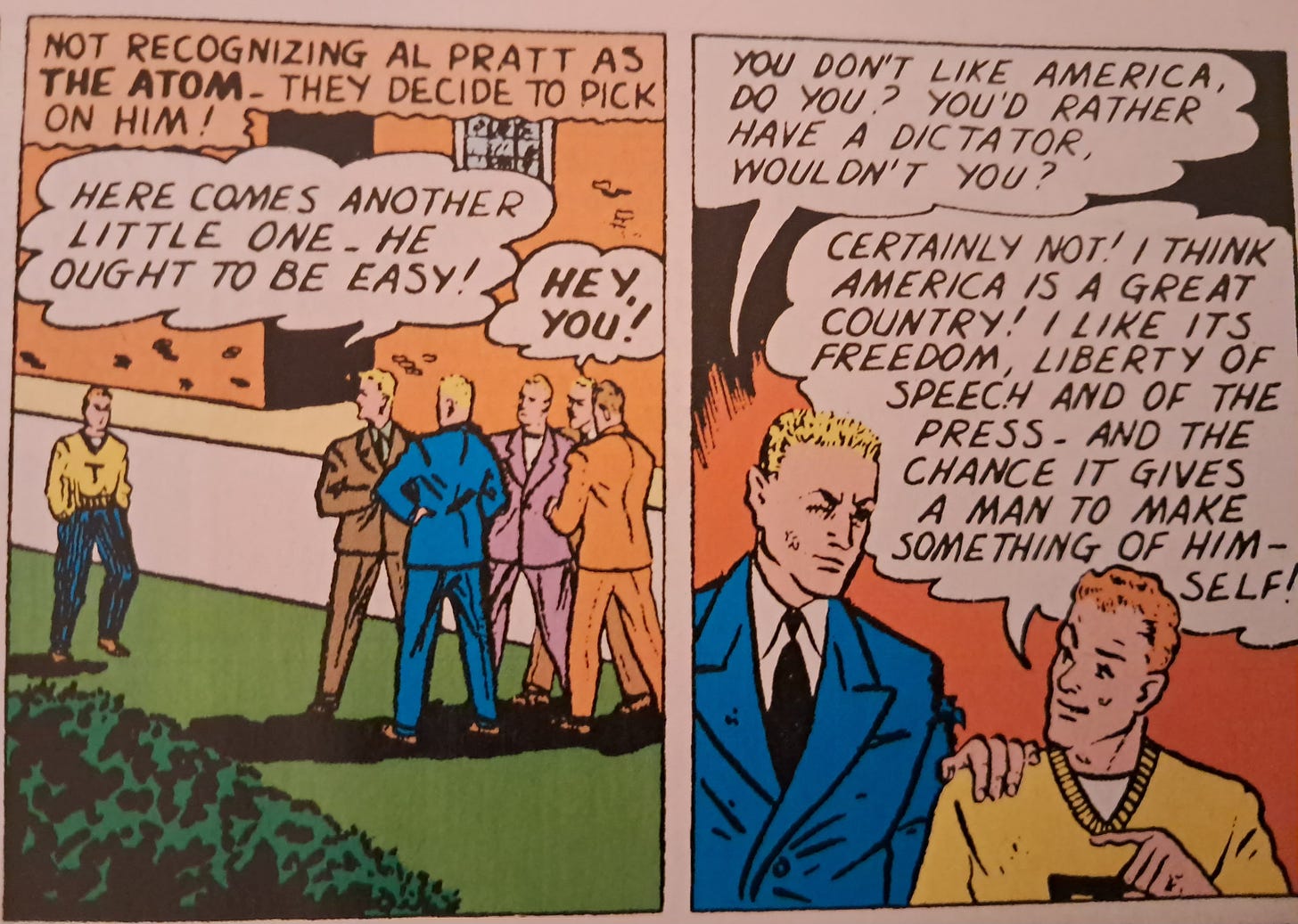

-"You'd rather have a dictator, wouldn't you?" A question needed to be asked now to some.