Holly Golightly is no superhero. She wears no cape and only briefly wears any literal mask. But she does have a secret identity, a persona she’s buried so deeply that no one will ever discover it.

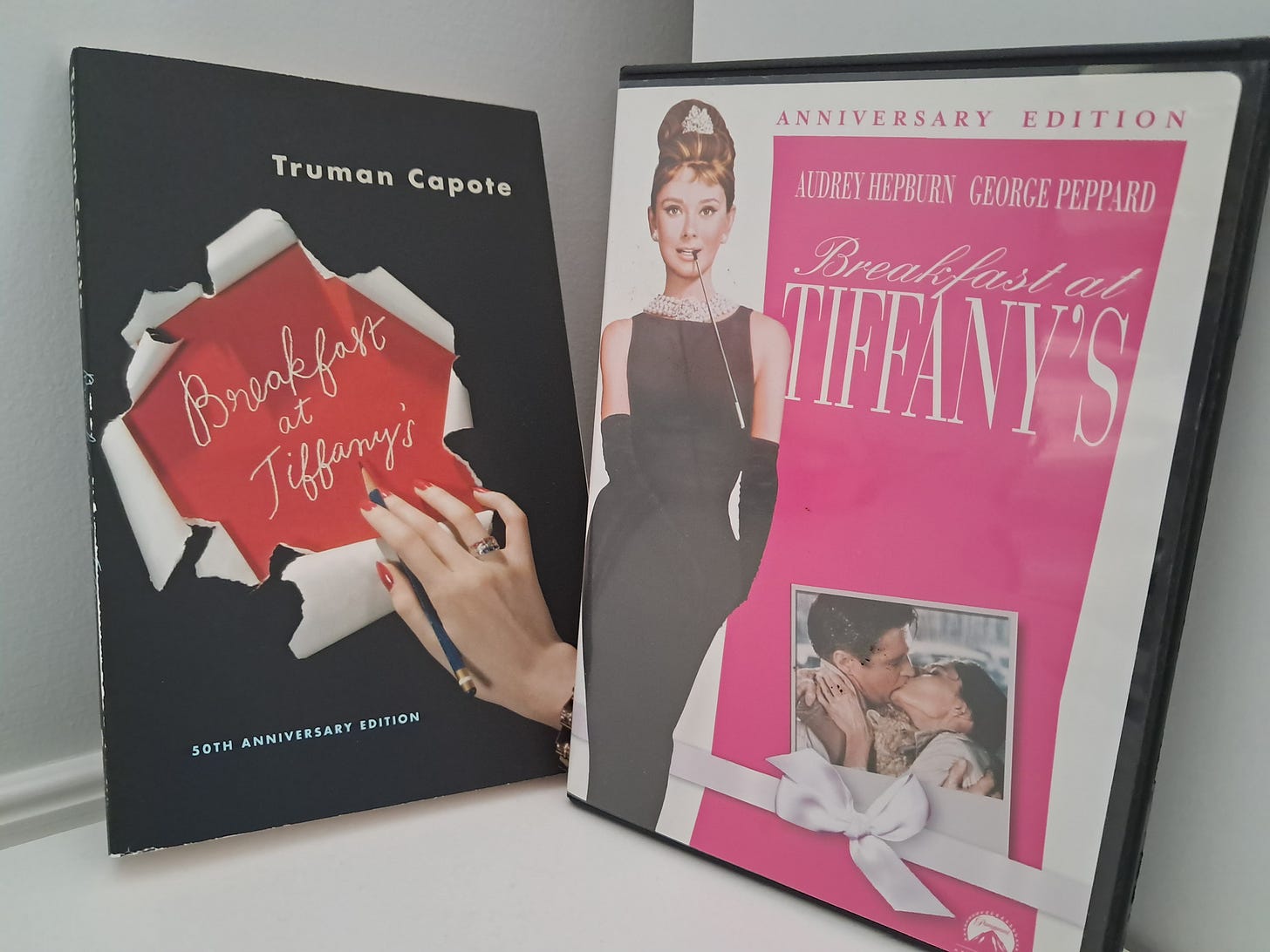

Maybe that’s why Breakfast at Tiffany’s rates as that most rare of gems: a romantic comedy I actually enjoy.

It’s hardly a typical romantic comedy. The 1961 film is more like a character study about friendship, with some romance shoehorned in. Audrey Hepburn gives a superb performance, possibly the best of her career. She portrays a Holly Golightly who’s beyond belief and yet also feels like a solid person.

Opposite her is George Peppard, who grounds the movie as our viewpoint character, a struggling writer named Paul Varjak. An organic friendship develops between these two, and it’s such a well-crafted relationship that the romance is almost superfluous.

Neither Holly nor Paul is looking for love, but both need a real friend, and they find that friend in each other. They come to care for each other as people. The big grand-finale kiss is little more than Hollywood spectacle compared to the deeper human connection they develop.

The fact that Holly initially insists on calling him Fred, after her brother, makes the romance angle kind of weird. It’s a seam the filmmakers neglected to cover up when adapting the book into a movie.

In the 1958 novella by Truman Capote, Holly and this struggling writer truly are nothing more than friends, and sometimes barely that. Paul isn’t even Paul. Holly calls him Fred, but otherwise he’s just our nameless first-person narrator. Movie Paul develops into his own character, but the nameless book version functions like a theatre set—he’s imbued with enough details to suggest the whole, but much is left to the imagination.

For example, this throwaway line hints at the narrator’s wider life outside of Holly:

First off, I’d been fired from my job: deservedly, and for an amusing misdemeanor too complicated to recount here.

We learn nothing about the job or the “misdemeanor.” The book leaves plenty of blanks to fill in, and we trust that a person exists within those blanks.

The narrator is not the subject of this literary portrait. Holly is. The narrator both observes and interacts with Holly, creating a detailed image in a short page count (87 in my edition).

Capote writes compelling physical description, deploying it not just to create an image but to suggest character as well. A soul lurks in the details.

Late in the book, the narrator glimpses Holly shorn of all artifice:

She looked not quite twelve years: her pale vanilla hair brushed back, her eyes, for once minus their dark glasses, clear as rainwater […].

Soon, though, Holly puts her mask back on:

The instant she saw the letter she squinted her eyes and bent her lips in a tough tiny smile that advanced her age immeasurably.

[…]

Guided by a compact mirror, she powdered, painted every vestige of twelve-year-old out of her face.

The makeup is mentioned not to show us what she looks like but to raise the questions of what it conceals and why. Holly holds the entire world at arm’s length, preventing the narrator—or us—from ever completing this literary portrait. Those gaps keep the character endlessly compelling.

The narrator observes her reticence in this wonderful, contradictory line:

Like many people with a bold fondness for volunteering intimate information, anything that suggested a direct question, a pinning-down, put her on guard.

And we see that play out here:

“Why are you crying?”

She sprang back, sat up. “Oh, for God’s sake,” she said, starting for the window and the fire escape, “I hate snoops.”

Holly’s background contains elements of Pygmalion and My Fair Lady. The musical debuted a mere two years before this novella’s publication, and it’s fitting that its movie adaptation also starred Audrey Hepburn. Holly was taught to behave in a more refined manner, but that education is a mere bit of backstory. My Fair Lady is basically the square root of Breakfast at Tiffany’s.

In the book, Hollywood talent agent O.J. Berman describes how he discovered young Holly and attempted to mold her into a star, giving her French lessons to tame her wild hillbilly accent. On the surface, the passage reads as straightforward backstory, but it merely colors in some of the character while also suggesting that there’s so much more to color in.

Berman tells the narrator:

“My guess, nobody’ll ever know where she came from. She’s such a goddamn liar, maybe she don’t know herself any more. But it took us a year to smooth out that accent.”

But then, right before she was about to test for a small role, Holly took off and moved to New York.

“She says you got to want it to be good and I don’t want it, I say well, what the hell do you want, and she says when I find out you’ll be the first to know.”

So, we get some intriguing information, but additional questions are baked into the information. We still don’t really know who Holly is, and Berman remains well aware of what he doesn’t know.

He perceives just how much she’s buried her original identity and gives us this memorable observation:

“She isn’t a phony because she’s a real phony. She believes all this crap she believes.”

Later, we learn that Holly has run away from her marriage to the too-old Doc Golightly, whom she met only because she and her brother were running away from something else. She’s always running away from one place to the next. But what was the original place? What initially set her running?

Doc Golightly tells the narrator what he knows, but we can’t be certain his information is correct. Even if it is, we’re still left only with broad strokes: Her name was Lulamae Barnes, and her parents died of tuberculosis. She and her brother Fred were sent to live with “some mean, no-count people” whom she “had good cause to run off from.”

What cause exactly? Capote wisely leaves further detail to our imaginations, which might be taking us down the wrong path anyway. Holly is constantly reinventing herself and her past, as demonstrated in this passage from the narrator:

I thought of the future, and spoke of the past. Because Holly wanted to know about my childhood. She talked of her own, too; but it was elusive, nameless, placeless, an impressionistic recital, though the impression received was contrary to what one expected, for she gave an almost voluptuous account of swimming and summer, Christmas trees, pretty cousins and parties: in short, happy in a way she was not, and never, certainly, the background of a child who had run away.

The novella ends on a more melancholy note than the movie. In both, Holly attempts to shoo away her nameless cat, not wanting to be tied down by anyone or anything, not even a pet. In both, she regrets this impulsive decision. But movie Holly corrects her error and finds the cat, as well as Paul’s lips. Book Holly merely comes to the realization that she and the cat belonged to each other after all, and the narrator promises to find him.

And he does eventually find the cat. The novella closes with these lines:

Flanked by potted plants and framed by clean lace curtains, he was seated in the window of a warm-looking room: I wondered what his name was, for I was certain he had one now, certain he’d arrived somewhere he belonged. African hut or whatever, I hope Holly has, too.

The cat finds a home and identity while Holly is again running away and presumably reinventing herself once more. Maybe twice more. Or multiple times. Her fate remains ambiguous, though we have hints of it at the beginning of the book, when the narrator hears news of her for the first time in years.

“She’s probably never set foot in Africa,” I said, believing it; yet I could see her there, it was somewhere she would have gone.

And that’s how the book and movie are similar: Both versions of Holly are larger than life and beyond belief, but both are so solid that we convince ourselves that we know this woman.

But no one knows who Holly Golightly really is. Her true identity remains a secret.

Recently I was talking to someone about the Japanese concept of aimai, or ambiguity. In art there is room to be deliberately mysterious sometimes: to leave people wondering. Holly seems to be that kind of character, which is becoming more rare in American cinema.

I haven't read/watched the book/film, but I enjoyed this look at how the film chose to adapt certain things - like giving the nameless narrator more character (pun intended 😆) in the movie!