The Unadaptable Sandman?

Sometimes, I'm happy to be wrong.

Imagine adapting the Broadway musical Hamilton into a movie. Would that work? Probably not entirely. It was created specifically for the stage, not for film, and something would inevitably get lost in translation.

I had a similar thought when I saw the first trailer for Netflix’s adaptation of Sandman, the classic comic book series by Neil Gaiman and a whole bunch of talented artists (Mike Dringenberg, Kelley Jones, Malcom Jones III, and so many others). It was such a perfect fit for the comic book medium—how on earth could a live-action series truly do it justice? Isn’t it sometimes okay or even preferable to leave a work in its original form?

DC Comics launched Sandman in 1989 as one of its “suggested for mature readers” comics, and it became the original crown jewel of DC’s Vertigo imprint, which editor Karen Berger founded in 1993. Vertigo redrew the boundaries of the types of stories comic books could tell, and it initially focused on horror and fantasy, both of which are abundant in Sandman.

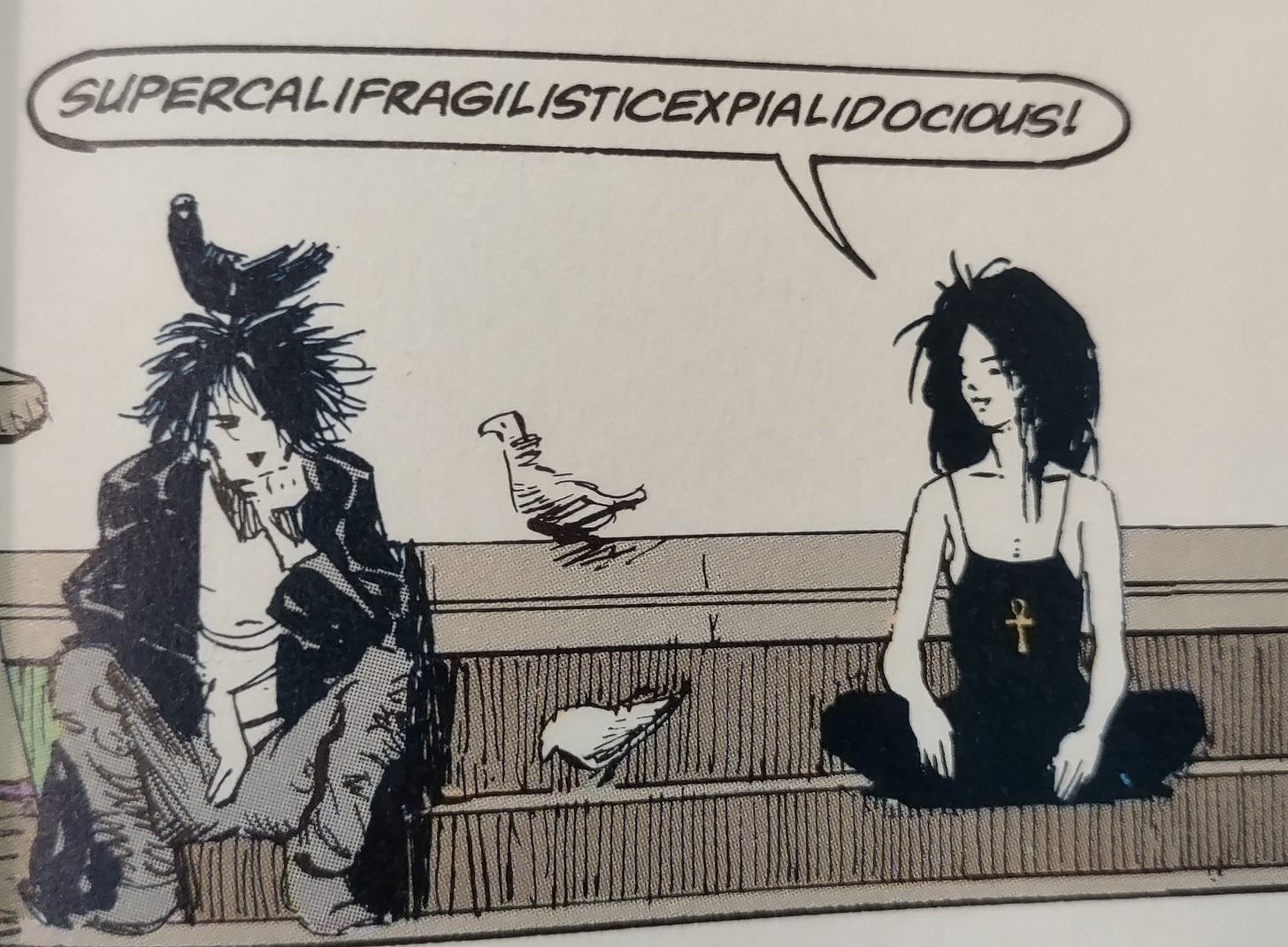

Sandman builds its own mythology. The central character, Dream, is one of the Endless, as are his siblings Destiny, Death, Destruction, Desire, Despair, and Delirium (formerly Delight). Each rules their own domain and lives up to their namesake. As such, Dream’s kingdom exists in the dreams of all living creatures, and Dream (also called Morpheus) is essentially a king of stories. The whole Sandman series is a love letter to storytelling.

Dream himself makes for an unconventional protagonist, in that he doesn’t always qualify as one. At times, he’s more like the connective tissue holding the series together. It’s sort of like if Rod Serling was a recurring character within Twilight Zone episodes rather than the show’s host.

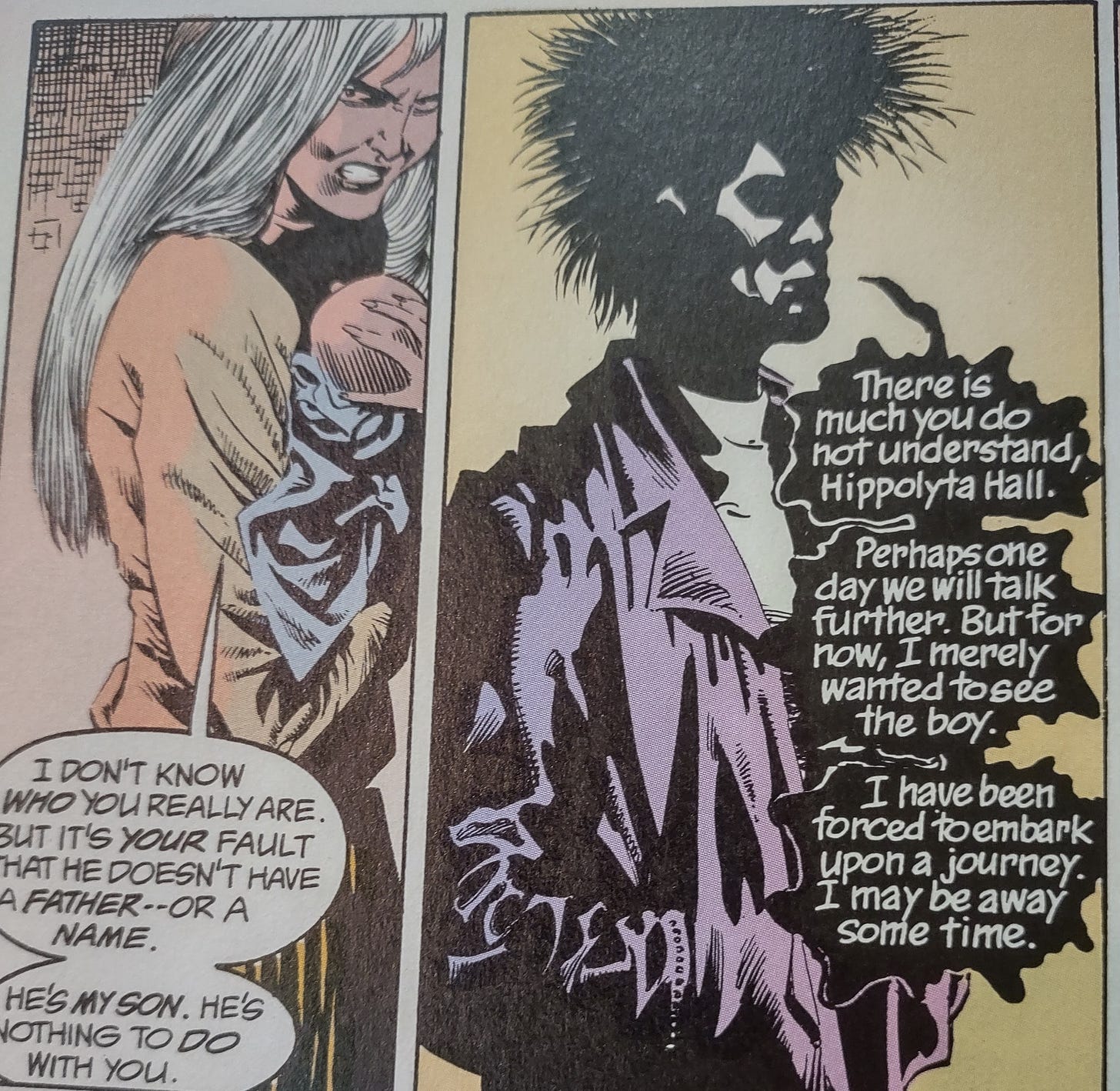

Sandman consists of short stories as well as longer arcs, but in both types, other characters typically serve as the protagonists. Whenever Dream acts, he acts as the catalyst of someone else’s story, whether intentionally or not. And when he acts, he often seems to think he has little choice in the matter.

A good example is the fourth Sandman trade paperback, Seasons of Mist.

(Spoilers ahead!)

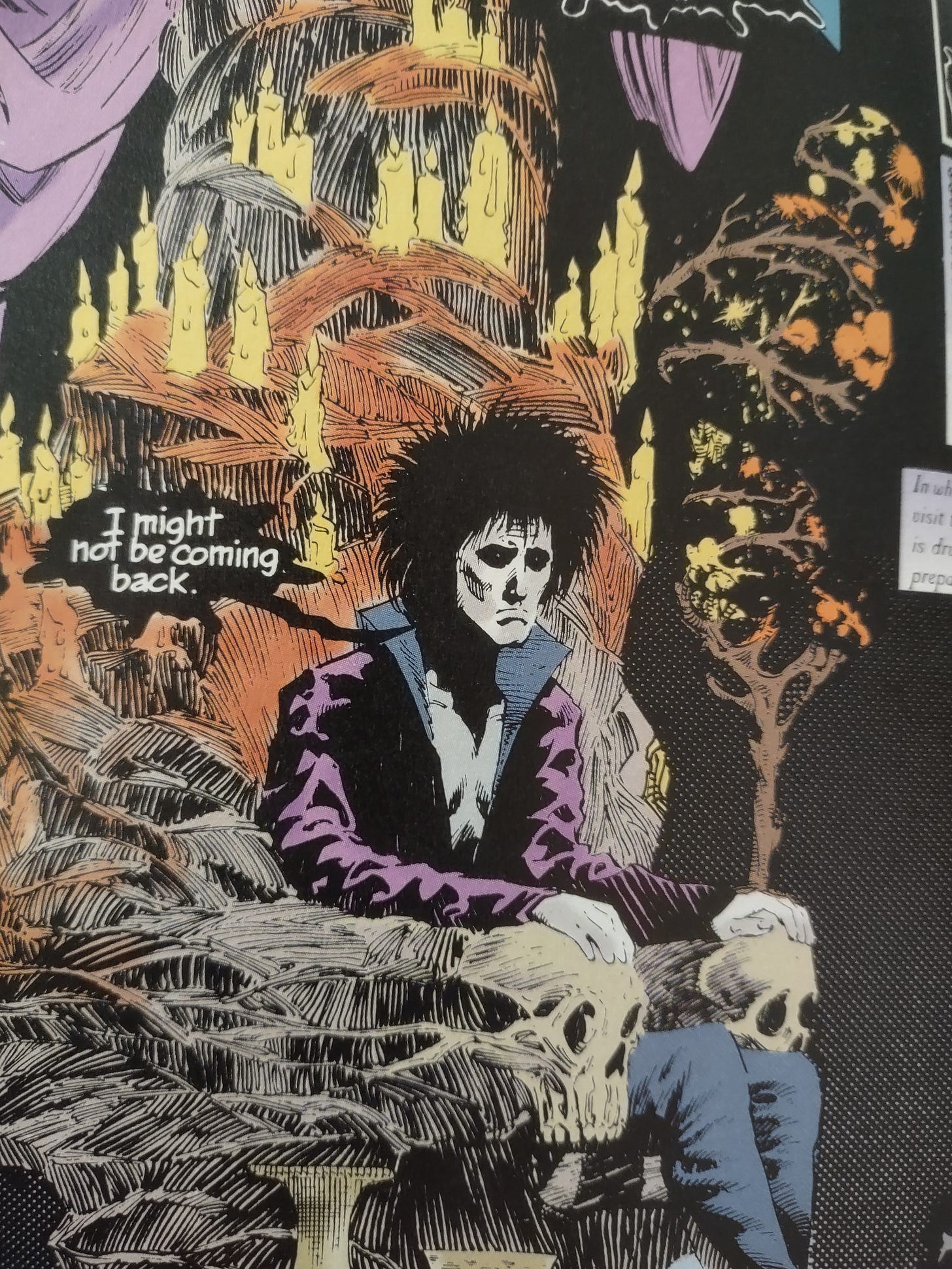

After a tense meeting with his family, Dream decides to free a former love interest whom he sentenced to Hell long ago, so he prepares to wage battle against Lucifer and all his demonic forces if necessary. Dream makes a big show of it, going on something of a farewell tour to say all his goodbyes in case he doesn’t return.

But then when he gets to Hell, Lucifer decides it’s time to retire. He closes up shop, sends all the denizens of Hell away, and gives Dream the key to Hell’s gate.

So, no great big battle. The story shifts gears from a potentially epic life-and-death quest into an impossible dilemma: What should Dream do with the key to Hell? Use it? Rule Hell himself? Give it away?

A colorful cast of immortal beings, ranging from demons to faeries to Norse gods, visits Dream’s kingdom to bargain for the key. Each party presents a compelling offer that gives Dream much to think about.

But then two angels tell Dream that they’ve received word from On High that they need to take the key. The decision is essentially made for him, and Dream hands the key over. Dilemma averted.

And with this story, Gaiman achieves something remarkable—anticlimactic twists that somehow remain interesting. They work because they provide springboards into new stories that offer just as many possibilities. Lucifer’s abdication of Hell leads into his own spinoff series, and putting faithful angels in charge of Hell raises thought-provoking questions about the nature of that realm and what it’s supposed to be.

These events result from Dream deciding he must right a past wrong. Ultimately, though, it’s not about him. He’s not the story—he is story. In all the Endless, Gaiman anthropomorphizes concepts, giving us a cast of unique, memorable characters.

The Endless all work best as graphic novel characters, where the union of writing, imaginative artwork, and distinctive lettering styles can bring them to life and properly distinguish them from the human characters and even other immortal characters.

So what about the Netflix series then? I still say the books are better and you should read them first. But I have to concede—everyone involved pulled off a solid show. They adapted what I thought was unadaptable.

The Netflix series is at its best when it adapts the short stories, and that’s really where it has the potential to expand upon the source material. The best episodes are “The Sound of Her Wings” (adapting issues #8 and #13) and “Calliope” (adapting #17). The former presents a faithful adaptation of two different standalone stories, but the latter stretches out a 24-page comic to 40+ minutes of screen time, giving the story more room to breathe.

That got me wondering if Sandman the streaming series might have worked best in an anthology format, with Dream as a sort of Super Rod Serling figure. But I could be wrong about that too. We’ll have to see how future seasons turn out.

The first season adapts the first two trade paperbacks, Preludes & Nocturnes and The Doll’s House. It’s not surprising that the audience ratings on IMDb take a dip once the season transitions from the first book to the second (as of this writing, anyway). I can imagine a decent chunk of the audience going “Wait, what? Do we have a new main character now? Why does this feel like a different show all of a sudden?”

But that’s Sandman. It’s a whole lot of things along the way, which is part of the comics’ charm.

So, I highly recommend the graphic novels (all ten volumes—but adults only), and I recommend the Netflix series if you enjoy the graphic novels. I’m on board for watching season two.