With Great Power Must Come Great Humanity

'Black Adam' failed to create a compelling protagonist, but Superman shows us the way.

I prefer superheroes to antiheroes, so I had skipped Black Adam in the theaters. And when I finally did watch it recently, that was mostly to see how the Justice Society turned out.

The movie didn’t leave a strong impression on me one way or the other. The recently cancelled CW series Stargirl did a much better job of showing what the JSA is all about, and it succeeded with a much smaller budget. As for Black Adam, I would have preferred to see him as the antagonist of a Shazam! sequel or an actual Justice Society movie.

David Swindle at God of the Desert Books reviewed Black Adam, and his criticisms sparked some thoughts, particularly the issue noted in the subhead: “How Can One Emotionally Relate to Invincible Demi-Gods?”

I agree about the movie, and yes, it is difficult to pull off a story with an ultra-powerful character as the protagonist. Black Adam, Captain Marvel, and Man of Steel all failed in this regard, and Thor has devolved into a clown in his latest movie appearances, so I can’t fault anyone for doubting that such characters can work as compelling protagonists. (Even when done well, these characters won’t appeal to everyone’s tastes, of course. Nothing wrong with that.)

Ultra-powerful protagonists can work, but they require several ingredients: humanity, morality, sacrifice, loved ones, self-restraint, clear upper limits to their great power, and foes who are even more powerful or smart enough that the hero’s brute force alone won’t win the day. The powers magnify the scale and scope, but these ingredients can keep the characters relatable.

Superman may be the obvious example, but he is indeed the best example. Plus, as the original superhero, he provides the template.

With all his tremendous power, Superman can do whatever he darn well pleases, but he still chooses to help people. The powers themselves may be an adolescent fantasy, but what’s more interesting for a broader audience is how he uses those powers. A great Superman story shows how someone that powerful can be that good.

Super-incorruptibility is Superman’s most important power. Unlike his many other abilities, it’s one he learned and honed, and it’s not one he can take for granted. His parents set the example of how a person should be, and Superman amplifies that example and shares it with countless others.

And it’s fun to watch a good man go toe-to-toe with an overpowered tyrant and ultimately prevail. It’s a whole lot more fun than watching two overpowered jerks pummel each other into submission, because when one is a character like Superman, the ideals win out as much as the strength.

DC Comics rebooted Superman’s continuity in 1986 to dispose of the clutter and the bloated Kryptonian lore that had accumulated over the decades. Writer/Artist John Byrne made a number of smart revisions in his Man of Steel miniseries (not to be confused with the movie of the same name) and subsequent comics.

Clark Kent was no longer a mask for Superman to wear between super-feats. Now, he was Clark Kent, and Superman was simply how he chose to use his powers. His adoptive parents were still alive and always willing to offer guidance, further anchoring Clark in humanity. His powers were streamlined (goodbye, super-ventriloquism) and clearly defined while remaining impressive. And for a while, Krypton mostly stayed out of the way.

Free of the clutter, the focus shifted to what’s far more compelling: how Clark grows into his role and responsibilities, how he adjusts to the burden that he has freely chosen, and how he sticks with it despite any setbacks.

Superman For All Seasons (1998), a four-issue miniseries by frequent collaborators Jeph Loeb and Tim Sale, explores precisely that. The book is set during Superman’s early days, and as the title suggests, it’s structured around the four seasons. A different character narrates each issue: Jonathan Kent, Lois Lane, Lex Luthor, and Lana Lang.

Pa Kent introduces us to a young man who was raised right and wants to do right. Lois describes a dashing man who’s too good to be true, and yet he is that good. Luthor contemplates a rival for the affection of Metropolis, a lonely man who can’t save everyone no matter how good his intentions are. And Lana tells us about Clark Kent, the kind boy she grew up with who’s still there inside that costume.

Together, the issues form a nice arc, guiding us from Clark’s initial desire to use his abilities to help the world, to his initial successes, to his first real defeat, to his acceptance that even though he can’t do everything, he’ll still do everything he can.

Superman may be bulletproof, but Loeb and Sale show us just how vulnerable the Man of Steel can be. They zero in on Clark’s humanity, and in doing so, they instill a sense of grandeur in Superman’s feats. And that’s basically what Lana tells us in her issue: To understand the super, you have to understand the man.

And the man can be hurt.

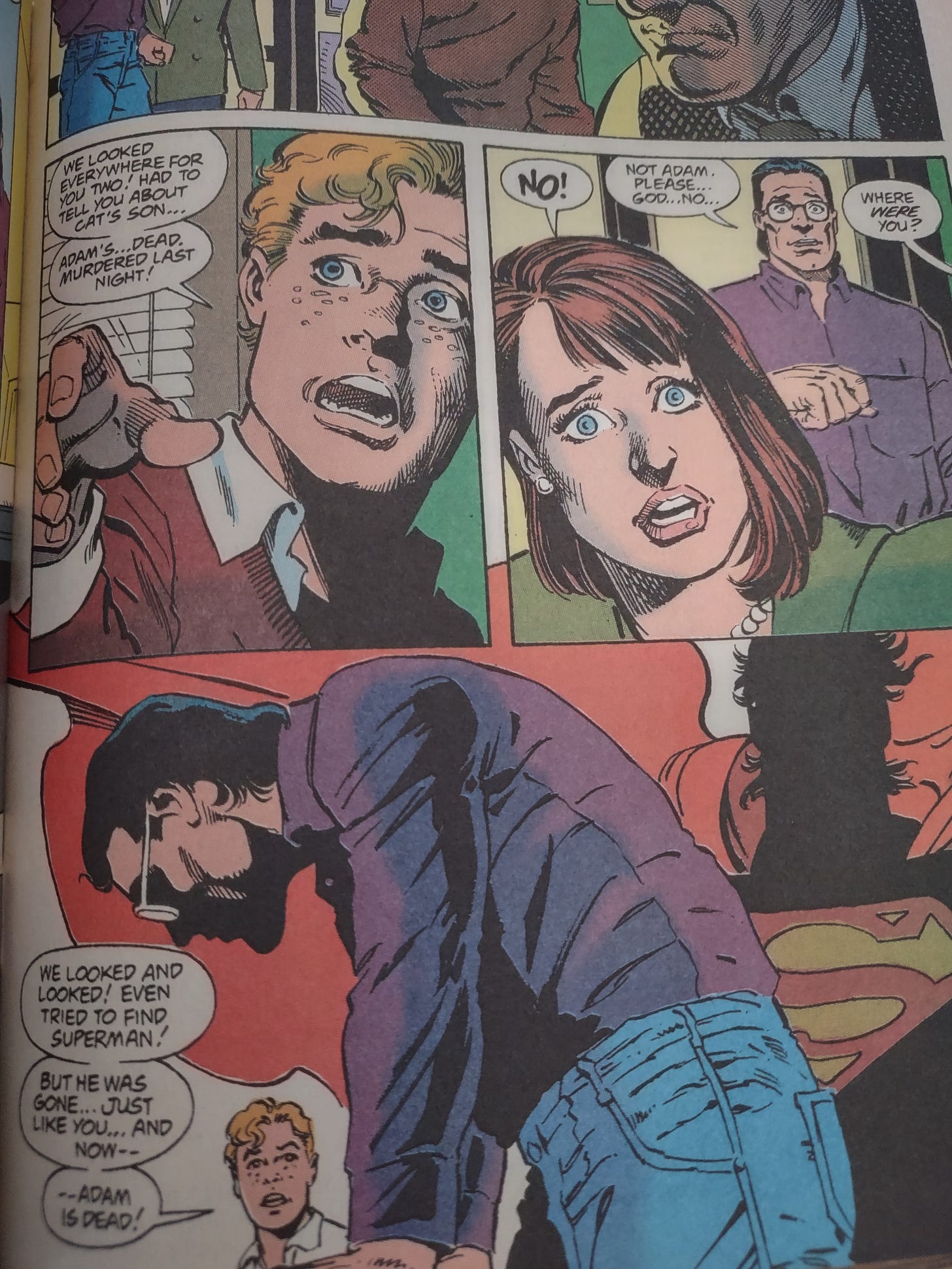

As long as Superman cares about people, anyone can wound him. The whole world depends on him, but even he can’t possibly be everywhere he’s needed. There’s always that risk that he could fail to save a friend or loved one.

Here’s an excerpt from Superman #84 (1993) by Dan Jurgens, in which Superman learns a friend’s son died while he was off doing other things:

In Superman: The Movie, Jonathan Kent dies of a heart attack. Clark, despite all his power, couldn’t do a thing to stop it, and that haunts him and further motivates him to do everything he can do to help people.

Compare this to Man of Steel (the movie), where that version of Jonathan Kent tells Clark not to save him from a tornado so he doesn’t reveal his powers to the world. And Clark lets him die, a creative decision that displays a fundamental misunderstanding of Superman’s appeal.

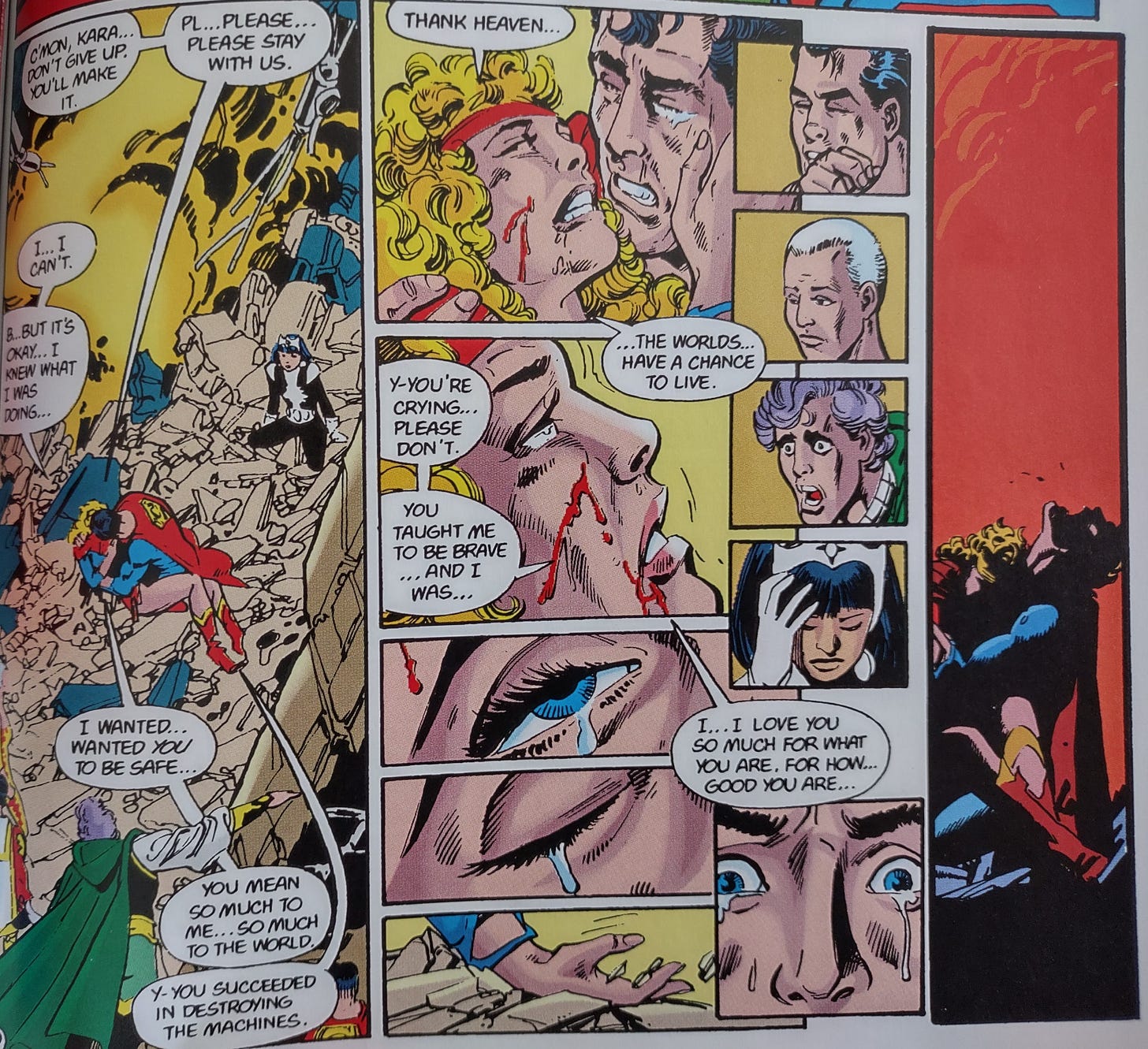

If Superman is going to fail, it should never be while standing idly on the sidelines. It should be something like Crisis on Infinite Earths #7 (1985) by Marv Wolfman and George Perez.

In this issue, a group of powerful superheroes wages a last-ditch campaign against the even more powerful Anti-Monitor, who’s already destroyed entire universes. Naturally, Superman is the first to reach the villain. Everyone expects him to be their best chance of taking him down and saving the remaining universes.

But Superman fails. The Anti-Monitor beats him, and beats him bad.

So Supergirl steps in and steps up. She’s thinking entirely selflessly. She wants to save her only living relative, not only because she cares about him but also because of what he means to the world. She’s spent her entire time on Earth living in his shadow, so she’s assuming she could never possibly measure up to his example.

But she does. She clobbers the Anti-Monitor, destroys his machines, saves those universes for the time being … and then she makes a mistake, but for the right reasons. While she’s got the Anti-Monitor on the ropes, she turns away to urge someone else to get to safety, and the Anti-Monitor exploits her distraction to fire the fatal shot. Supergirl dies exactly as a hero should—putting others first and herself last.

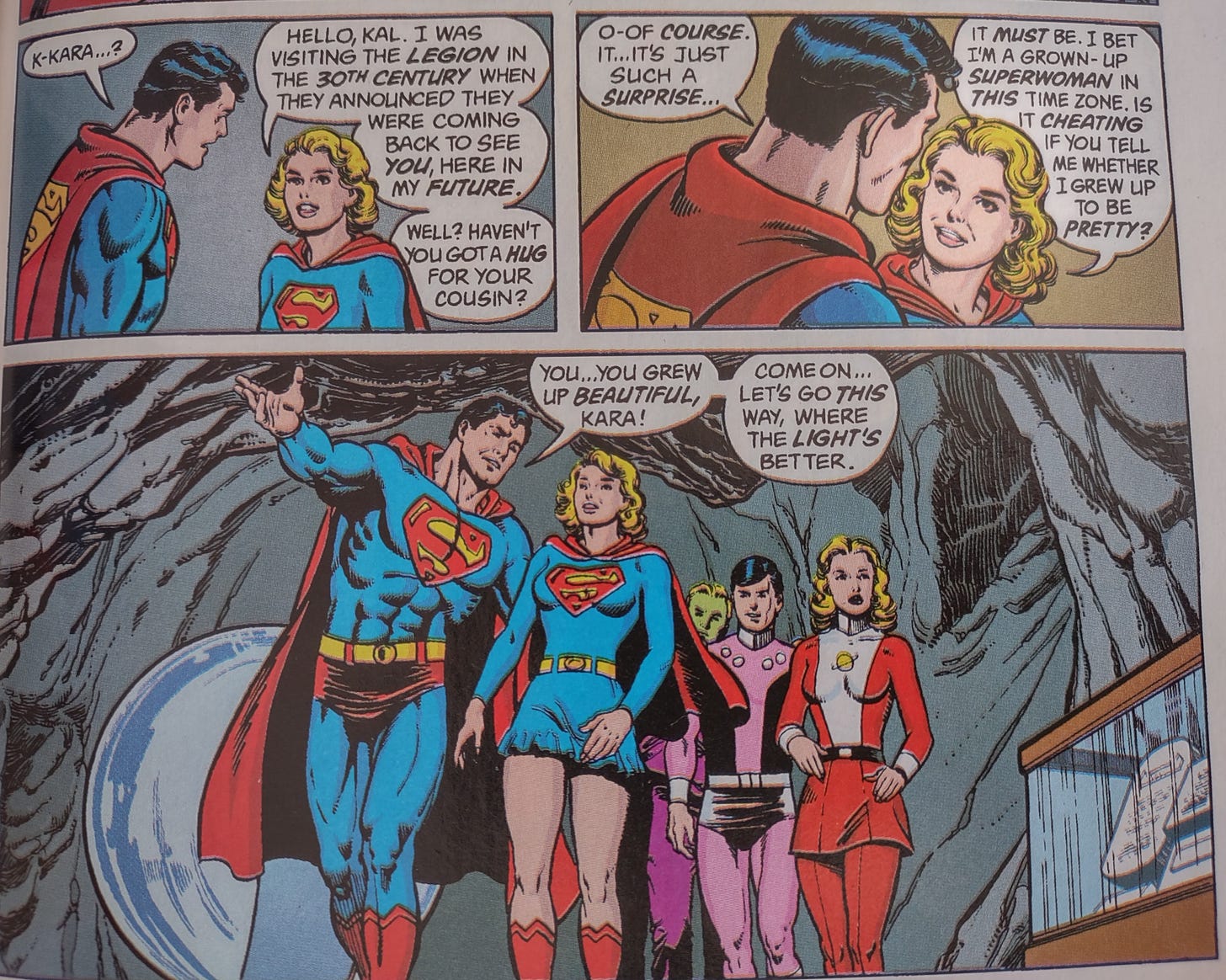

DC would eventually introduce a different Supergirl and then another who was closer to the original. But in this continuity, this was the definitive ending for this version of the character. This Kara never came back from the dead, which was confirmed during the final Silver Age Superman story, “Whatever Happened to the Man of Tomorrow?” (1986) by Alan Moore and Curt Swan. In one scene, a very young Supergirl time-travels to Superman’s present and breaks his heart into a million pieces.

Superman Annual #11 (1985)—by the Watchmen team of Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons—shows another way to hurt Superman. It’s Superman’s birthday, so Wonder Woman, Batman, and the then-new Robin (Jason Todd) visit him at the Fortress of Solitude, all bearing thoughtful presents. What do you get the man who seemingly has everything? The villainous alien Mongul gives Superman a life of contentment, but the catch is that it’s all imaginary.

A symbiotic plant called the Black Mercy traps Superman in his own head, where he’s living a perfectly normal life on a Krypton that never exploded. He has a wife and two children, and the weight of the world isn’t constantly on his shoulders. It all feels so real and satisfying.

But outside that fantasy, Mongul begins his quest for world domination by taking on Wonder Woman and the Caped Crusaders. To save his friends, and the world, Superman must abandon the peaceful life he always wanted, rejecting a loving family in favor of his Fortress of Solitude. And this makes the final battle against Mongul all the more meaningful.

The comic is so good that Justice League Unlimited adapted it into an animated episode.

Black Adam was indeed too remote and godlike in his movie, but Superman and other powerful characters can captivate us when they act fundamentally human.

For additional Superman thoughts, please see these earlier posts:

Evidently, I spend too much time thinking about Superman.

You explained perfectly what I couldn’t express about why the movie Man of Steel made me angry. In addition to the thought Superman should not kill, he would also not put his secret identity ahead of saving lives.

Loved the essay - perfect counterpoint to people who think that Superman is boring because he's "too perfect" or "too invincible"!