Batman in Prose

Tim Burton’s Batman, that is.

Welcome to And the Quest for Pop Culture, where I explore various movies, TV shows, books, and comics. Looking for a different topic or original fiction? Check out the navigation page.

As I’ve said before, movies are not the best medium for ongoing superhero sagas. Too little screen time, too much elapsed time between movies. That misses a lot. Superheroes tend to lead busy lives, after all.

Tim Burton’s version of Batman got only two movies. (The Joel Schumacher movies should be quarantined within their own series.) Surely, Michael Keaton’s Batman saw some action between Batman and Batman Returns. There’s no way he was just brooding in Wayne Manor the whole time.

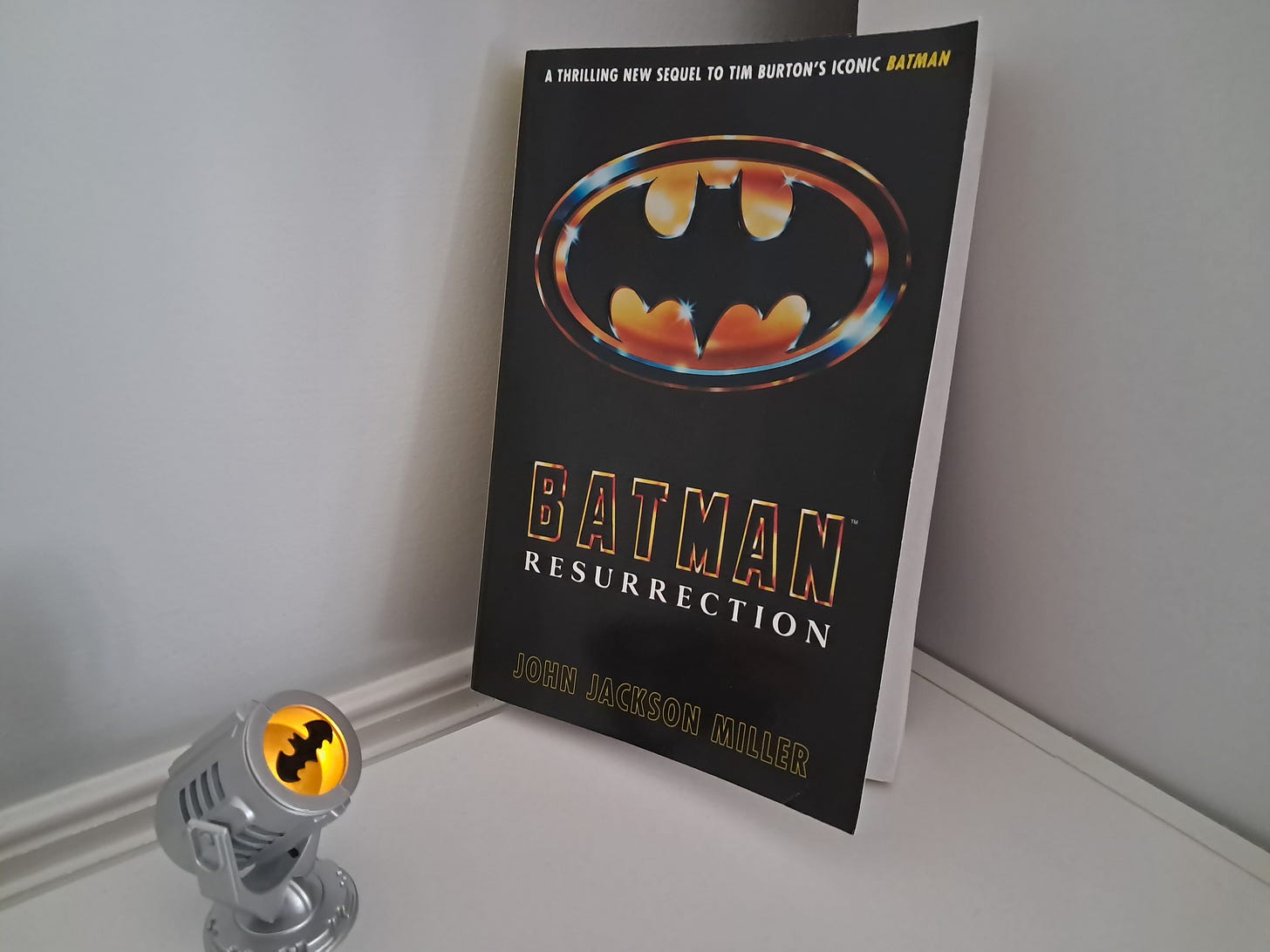

Fortunately, we have the wonders of tie-in media to fill in the gaps. A series of novels debuted just last year. John Jackson Miller wrote Batman: Resurrection as well as this year’s sequel, Batman: Revolution.

I recently read and enjoyed the first book. The Batman ’89 iteration is not the definitive Batman for me (as I’ve previously written), but he has his merits, which become more evident within the breathing room of a novel.

Whereas Burton was no comic book fan, Miller clearly is. He draws inspiration from the earliest Batman comics to expand the world of Burton’s movies.

Resurrection takes place between the two movies. Gotham is still reeling from the Joker’s reign of terror. Numerous victims remain in recovery, particularly those who were exposed to his tainted cosmetics. Bruce Wayne, naturally, donates considerable funds for their treatment. Meanwhile, a group of criminals calling themselves the Last Laughs carry on the Joker’s anarchic legacy.

In the grand Bat-movie tradition, the book introduces Batman ’89 versions of two classic foes: Hugo Strange and Clayface. Both fit neatly into the aftermath of the first movie. Strange, operating under an alias, treats the Joker’s victims to serve his own ends. One of the more unusual victims is Basil Karlo; the Joker’s chemicals transform the failed actor into the shapeshifting Clayface.

Karlo is misguided rather than evil, making him a more interesting antagonist, and the theatre connection feels appropriate. Batman is inherently theatrical, after all.

In comics, the Batman of the 21st century has experienced significant power creep (ironically, given the absence of actual super-powers). He’s become so amazing at so many things that, too often, he might as well be superhuman. Not here, though. This is a very human Batman, one who has physical limits. He gets tired, even exhausted. He makes mistakes. He has nightmares. He misses his girlfriend, Vicki Vale, who never could get used to his double life. The man even has a dry sense of humor from time to time.

He’s almost like the Batman of the ’70s and ’80s comics, which is a fine Batman to be. The main difference is that, in line with the movies, this Batman depends a bit more on technology and a bit less of innate physical skills such as martial arts expertise. But he does possess a sharp mind. Miller provides ample opportunity for Batman to show off his detective skills, which is always welcome.

Still no Robin in this Bat-world. Alfred is the real sidekick here, with more to do than in either movie. We also get a better sense of how this Batman collaborates with Commissioner Gordon.

The third-person narration explores several viewpoints, on both sides of the law. This does slow down the pace a bit, perhaps slightly too much at times, but it’s worth it for the stronger character development.

Additionally, Miller works in some setup for Batman Returns, giving a minor role to Max Schreck (the Christopher Walken character), hinting at the Penguin, and showing us a pre-Catwoman Selina Kyle. He also sets up the villain of the next book, making it even more apparent that this is separate from the Schumacher movies.

Part of Hugo Strange’s scheme is straight out of the early comic books. So is Bruce Wayne’s girlfriend, Julie Madison, who was the original Bat–love interest. Julie is basically a new character here, and she mostly serves to make the reader wonder, “Wait, what happened to Vicki Vale?”

Whereas movies must make do with finite resources, a novel’s special effects budget is limited only by the writer’s imagination. Even so, it’s important not to go overboard. Miller shows the right level of restraint, introducing elements that would have been too expensive to pull off convincingly circa 1990, but avoiding anything outlandish enough to break Batman Returns.

Miller brings Tim Burton’s Batman closer to his comic book roots without sacrificing the distinctiveness of those movies. It’s a nice best-of-both-worlds approach, resulting in a fun time for Bat-fans of any medium. I may have to pick up the sequel at some point.

As for the two movies, here’s an old post from a couple of years ago:

I remember reading a novelization of No Man’s Land which was better than the comics. Tighter, fast trimmed. And I remember reading a Batman story where he tracks down child sex traffickers. Not a great Batman book but I did subsequently learn about this horrible crime. I was not out less ignorant of it and of how widespread it is.

"Too little screen time, too much elapsed time between movies. That misses a lot. Superheroes tend to lead busy lives, after all." This is where television (and particularly animation) fills the gap with its episodic nature. A superhero creator can develop and define a fictional universe there and explore depths of character in ways a movie doesn't allow for (Craig McCracken did this with "The Powerpuff Girls": the series was about character-based narratives, while the companion movie filled in the background the main title sequence only hinted at, and was better for it.)