‘Joker’ and the Madness of Superfluous Sequels

They don’t get away with it a second time.

The first Joker movie succeeded because it isn’t really a Joker movie. It’s a 1970s-style “guy crushed by society until he snaps” film wearing Joker makeup. The Batman connection feels more like a marketing gimmick than anything else. And, to be fair, the marketing gimmick worked.

More important, though, the original movie has something to say. It explores the intersection of mental illness, poverty, and class conflict, and it seems genuinely interested in these topics. Containing not a single element of fantasy or science fiction, it is not a superhero movie at all, and it’s barely a supervillain movie.

Joker is about a mentally unstable man, initially neither good nor bad, falling through the cracks of society and becoming a deranged killer. The movie does not portray him as a hero, though anti-rich activists latch on to him and view him as a sort of righteous avenging figure, which in turn further emboldens him. Joker—or Arthur Fleck, as he’s named here—remains apolitical himself. He just wants to be noticed and loved, and he stumbles down the darkest path toward that end.

Exploring the origins of evil is a worthy theme in fiction, and it’s a difficult one to pull off. Joker does not invite audiences to cheer on Arthur; it puts audiences in his unreliable head and allows them enough room to recoil in horror at what he becomes. If anything, it implies that perhaps we should be kinder and more compassionate to the various people we meet on a daily basis.

Joker is not an entertaining movie, but it’s a worthwhile one. Just don’t try to fit it into any Batman canon. It’s comparable to DC’s Elseworlds imprint, which offers alternate versions of familiar characters, such as a Victorian-era Batman or a possible future Superman who had lost his way.

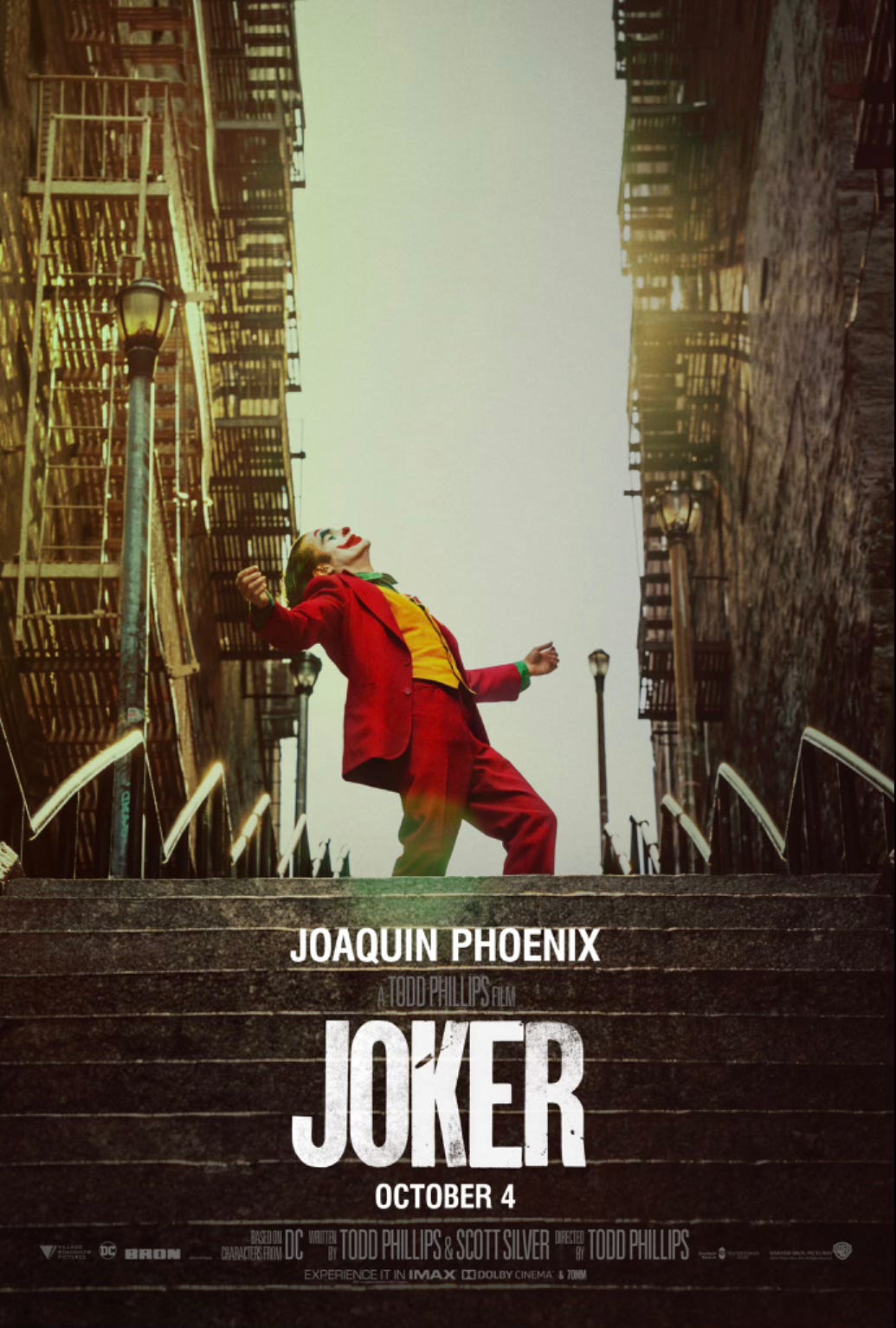

A fully original story might have made for a stronger film. Nevertheless, director Todd Phillips crafted a solid done-in-one movie that feels complete. It says what it has to say and leaves just enough ambiguity to merit a second viewing. Joaquin Phoenix deserved his Oscar for playing Arthur/Joker. Great work, guys. Now let’s move on to new projects …

Oh, wait. It made money.

So now, precisely five years later, we have Joker: Folie à Deux. The acting and cinematography are again excellent. And that pretty much exhausts all the praise I can give it.

(I’ll avoid any significant spoilers, but read at your own risk if you haven’t watched it yet.)

Whereas Phillips clearly had a story he wanted to tell the first time, this movie feels like it’s still searching for another worthwhile story. There’s plenty of visible effort. But this movie can’t escape the fact that it’s an unnecessary sequel. It never discovers its artistic reason for being.

The big draw this time is Lady Gaga as Harley Quinn, an inspired casting choice. Or it would have been if the movie had aimed for the traditional Joker/Harley dynamic, which is really all the movie needed to do.

Paul Dini and Bruce Timm created Harley Quinn for Batman: The Animated Series, and they gave her an excellent origin story in a 1993 comic book one-shot, Batman Adventures: Mad Love. Harleen Quinn was a psychologist interning at Arkham Asylum in hopes of exploiting one of the high-profile inmates for a sensationalistic tell-all book. The Joker became her patient, but over the course of their sessions, he manipulated her into falling in love with him and turned her toward an unhinged life of crime.

That’s a strong basis for a movie right there—the Joker’s gradual corruption of Harley as he drags her down into his madness. Something like that could have worked quite well in an adult-themed, R-rated movie with a strict no-Batman rule. We could have had a quiet, gripping psychological drama that explored the infectious nature of evil. All Joker: Folie à Deux needed to do was flesh out the flashback scenes of Mad Love.

You had one job, movie.

Instead, Harley, or “Lee” here, is already obsessed with the Joker when we meet her; she requires no corruption. If anything, she’s corrupting him. I didn’t realize he still needed more of that.

And that points to a significant problem. The sequel attempts to explore the duality of Arthur Fleck and Joker, but this decision comes with an unfortunate side-effect—a regression of Arthur’s development from the previous movie.

You thought he had completed his transformation into the Joker last time? Nope, now we’re not so sure.

A Looney Tunes–style cartoon short kicks things off and soon takes a Jungian turn, pitting the Joker against his own shadow. A mix of prison drama and courtroom drama fills the bulk of the runtime. Musical numbers keep interrupting the story without contributing much, despite the talent of Lady Gaga—it needed to either commit to being a full-fledged musical or limit itself to a single grand musical number. It feels all over the place even though the scope has narrowed to these constrictive settings.

Gotham City lived and breathed in the previous movie. It was a grungy, dirty place, not somewhere you’d want to spend your vacation, but it was a complete physical city. We lose that here, as we’re mostly stuck in prison, court, and Arthur’s head.

Joker: Folie à Deux delivers the occasional good scene along the way. It just never solidifies into a meaningful whole. The tight focus of the first movie—that compelling drive of This is a story we want to tell—gone. Instead of intentionally disturbing us, it unintentionally leaves us with a vague sense of pointlessness.

In the absence of Batman, this Joker’s greatest foe is financially mandated sequels. Sometimes, it really is okay to just make one good movie and leave it at that.

Well, marking that one off my list. I might go and watch the Joker movie now, actually; I'm intrigued, but this one like you say just seems pointless. "In the absence of Batman" really says it all, doesn't it.

Your thesis is here is spot on — the first should have been it. Not everything needs a sequel.