A good comedian conveys an important message: “Don’t take yourselves too seriously, and I won’t either.”

That’s basically what Seinfeld did for nine seasons. It showed us how ridiculous we all are, but not in an “Oh God, I hate people” way. It had more of an “Aren’t people funny?” tone.

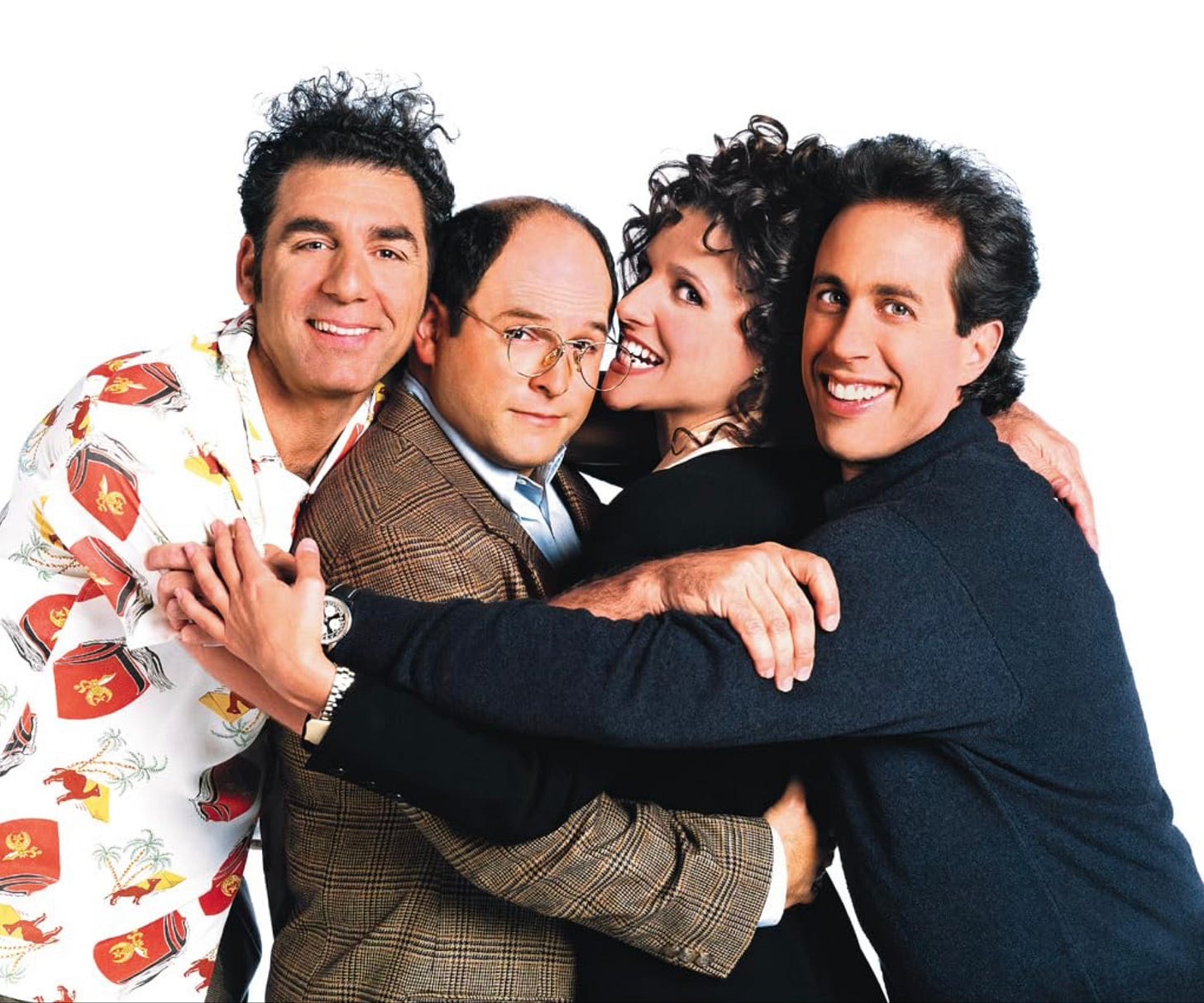

Jerry Seinfeld plays a fictional version of himself—a comedian living in New York City who frequently hangs out with his lifelong best friend, George Costanza (Jason Alexander), a neurotic chronic failure who’s based on series co-creator Larry David. Kramer (Michael Richards) lives across the hall and perceives little in the way of boundaries. And it was clear that the 1989 pilot episode was missing something—namely, a woman who’s directly involved in each episode’s events—so ex-girlfriend-turned-friend Elaine (Julia Louis-Dreyfus) arrived in the next episode. And a classic quartet clicked into place.

The series focuses on humorous observations about everyday life and situational etiquette—everything from double-dipping to various breakup protocols to who has rights to a parking space—as all sorts of colorful characters come into contact with Jerry, George, Elaine, and Kramer.

Jerry and friends are often passing judgment on these people—whether the individual in question is a close talker, a low talker, a high talker, a re-gifter, or a Soup Nazi—but the show knows full well that Jerry, George, Elaine, and Kramer aren’t such wonderful human beings either. As they comment on other people’s weird quirks and flaws, we laugh at their weird quirks and flaws. And we might recognize ourselves at any point along the way. While we’re hopefully not as petty or thin-skinned as George, he represents our less dignified impulses (softened just enough by Alexander’s excellent performance—it’s a crime that he never won an Emmy).

When comedy laughs at everyone, it ultimately judges no one. We’re all flawed and messed up in our own ways, and we’re all just trying to figure things out. Comedy deflates our pretensions and reminds us to stay humble.

To achieve this, Seinfeld eschews all sentimentality. Many great sitcoms, such as Frasier, have balanced out the humor with sincere, heartfelt moments, and they were stronger shows for it. But Seinfeld doesn’t need that. It just zeroes in on the comedy and exposes our countless foibles. The hugs are few and far between. Seinfeld cares only about what’s funny.

The exception is the season two finale, “The Deal”—the one episode that actually does contain genuine human sentiment, as Jerry and Elaine try to figure out how to have sex without ruining their friendship.

Weirdly enough, the episode (and season) ends with the two of them in a relationship. The next season leaves it a little ambiguous for a few episodes until Jerry tells his parents that he and Elaine decided they work better just being friends. According to Seinfeld and David’s DVD commentary, the network wanted Jerry and Elaine to get together, which David had resisted until he discovered some inspiration from his own life experience. (Amusingly, David was quite surprised to learn that he had left Jerry and Elaine in a relationship at the end.) So, they were appeasing a network note, and then they swept it under the rug as quickly as possible and went back to doing their own thing.

In the season nine episode “The Serenity Now,” the series mocks its own heartlessness. Jerry’s girlfriend of the week (fittingly played by Full House’s Lori Loughlin) encourages him to embrace his feelings. And he does. And he becomes a boring sap.

The show had excellent guest stars throughout its run. Among the MVPs is Wayne Knight as Newman, Kramer’s friend and Jerry’s nemesis. Additionally, Jerry Stiller and Estelle Harris are wonderfully chaotic as George’s parents, and you’ll find plenty of familiar faces in each season: Michael Chiklis, Jane Leeves, Teri Hatcher, Bryan Cranston, Debra Messing, even the New York Mets’ Keith Hernandez. And there are plenty of guest actors you wouldn’t recognize, but they nail their parts.

Some episodes are like The Twilight Zone for mundane matters, such as being unable to find your car in a parking garage (season three’s “The Parking Garage”) or suffering an interminable wait in a restaurant despite being repeatedly told that a table will be ready in five, ten minutes (season two’s “The Chinese Restaurant”).

Did the car disappear into an alien dimension? Is the maître d’ playing diabolical mind games? No, life just makes no sense sometimes, and it’s funny.

The show even references The Twilight Zone in the season eight episode “The Van Buren Boys,” in which Jerry dates a very attractive woman … but everyone else seems to think there’s something wrong with her and assumes Jerry is taking pity on this poor woman. Neither Jerry nor the audience can tell what’s wrong with her, and it drives him crazy. It’s Bizarro “Eye of the Beholder.”

It took the show a few seasons to find its footing, and when it did, Seinfeld and David settled into a reliable structure for each episode. The main quartet would get involved in a few separate plotlines, which would end up intersecting and colliding with each other by the climax. It’s life as a pinball game.

For instance, in the season five episode “The Puffy Shirt,” we have these threads: Kramer dates a low talker who speaks so softly that she’s incomprehensible. Elaine gets Jerry a gig on The Today Show promoting a Goodwill clothing benefit. George, miserable about needing to move back in with his parents, stumbles into a promising career as a hand model. And the specter of an oddly puffy shirt lurks throughout the episode, like Jaws waiting to devour everything.

Jerry, while politely nodding along to the low talker, inadvertently agrees to wear a shirt of her design when he appears on The Today Show. It’s a puffy shirt that makes him look like a pirate, but stores order the shirt based on Jerry’s promise to wear it. During the interview, the ridiculous attire steals focus from the clothing drive, prompting a frustrated Jerry to disavow the puffy shirt on air, which of course greatly upsets the low-talking designer. George, riding high after a successful hand-modeling debut, arrives in Jerry’s dressing room right after the taping to share his good fortune. But when he sees the puffy shirt, he laughs and mocks it—right in front of the low talker. She shoves George onto a hot iron, which burns his moneymaking hands and ruins his modeling career right at the outset. Elaine loses her position on the Goodwill committee, and Kramer breaks up with his girlfriend. Stores cancel orders for the puffy shirts, so the shirts end up going to … Goodwill.

The series has stronger continuity than I remembered, but each individual episode stands on its own. Seasons four and seven have the most serialization. The storyline about Jerry and George’s “show about nothing” carries through the former, and George’s engagement to Susan carries through the latter. But if you started either season in the middle, you wouldn’t be lost. Everything is sufficiently self-contained.

The catchphrases, too, are mostly self-contained. There are some character-specific ones that recur throughout the series, such as Elaine’s “Get OUT!” as she shoves one of the guys (with increasing strength as the series progresses). The episode-specific catchphrases, however, have their moment and then they’re seldom, if ever, referenced again. No constant callbacks here.

Fans of the show would reference these catchphrases frequently, though, to the point where it’s now cliché to say, “Not that there’s anything wrong with that!” But in the original episode (season four’s “The Outing”), it was a brilliant and funny way of skewering homophobes and the politically correct alike in a single great line. It did its job, and the show moved on.

Seinfeld had no interest in teaching any lessons to its audience. It was not one to tackle political or cultural issues unless it found some unique comedic angle to mine. This exchange from season eight’s “The Yada Yada” sums up the philosophy:

Jerry: I wanted to talk to you about Dr. Whatley. I have a suspicion that he's converted to Judaism just for the jokes.

Priest: And this offends you as a Jewish person?

Jerry: No, it offends me as a comedian!

The show shines when it embraces an absurdist flair without going too overboard. The season three episode “The Library” features Lt. Bookman, a hardboiled library cop who takes missing books very seriously. Placing an old-school detective in a library is so delightfully ridiculous. The season five episode “The Marine Biologist” ends with one of the greatest monologues in the entire series, as George recounts how he saved a beached whale after a lie caught up with him.

Superman references pepper the series. Seinfeld is a fan, and really, who can blame him? The season six episode “The Race” includes Jerry dating a woman named Lois and having way too much fun calling her Lois, and the main theme from Superman: The Movie plays at the end. In season eight, we meet “The Bizarro Jerry”—the episode leans into the lore of Bizarro Superman as it introduces Elaine to opposite versions of Jerry, George, and Kramer.

Occasionally, the show flirts with dark humor. George shoves women and children aside to escape a fire in season five’s “The Fire.” In season seven’s “The Rye,” Jerry mugs an old woman for a marble rye. There was also that time Jerry drugged a girlfriend so he could play with her vintage toy collection while she slept it off (season nine’s “The Merv Griffin Show”). There are even a couple of deaths.

For the first seven seasons, the collaboration between Jerry Seinfeld and Larry David provided much of the magic. Seinfeld brought a more colorful, cartoonish outlook while David supplied a darker edge. Together, they achieved the right balance, a mix of “Isn’t life so delightfully absurd?” and “Ugh, life is so absurd.”

David left the show after the seventh season, and Seinfeld continued as the showrunner for the final two seasons. It was like Paul McCartney without John Lennon—still plenty of great stuff, but it was no longer the Beatles.

However, David returned to write “The Finale,” the double-length final episode that was disappointing when it first aired, but it works better in hindsight without all the hype. While it doesn’t rank among the best episodes, the concept feels appropriate.

Having rejected sentimentality, Seinfeld couldn’t do the conventional “We’re going to miss this place—and each other!” sitcom series finale. No tears allowed here. No fond farewell hugs.

Instead, the quartet laughs at a fat man while he’s getting mugged, so they get arrested for violating a Good Samaritan law. During their trial, the prosecutors bring in various people the gang has run afoul of over the past nine seasons. The old lady Jerry mugged is merely the first of many witnesses. The parade of guest stars celebrated the series without requiring any box of tissues.

After the guilty verdict, the judge tells them:

Judge: I can think of nothing more fitting than for the four of you to spend a year removed from society so that you can contemplate the manner in which you have conducted yourselves. I know I will. This court is adjourned.

Jerry, George, Elaine, and Kramer conclude the series in a prison of their own making … which is how Seinfeld characters often live their lives.

But there is a way to escape such a prison, and that’s by not taking ourselves too seriously. Even though Seinfeld doesn’t want to teach us anything, that is the show’s one true lesson.

What a well written article. Thanks. Right amount of facts, helpful to those who may not be show followers.

Enjoyed reading your pieces on 'Seinfeld' and 'Frasier'. Unbelievable to think Jason Alexander never won an Emmy!