Welcome to And the Quest for Pop Culture, where I explore various movies, TV shows, books, and comics. Looking for a different topic or original fiction? Check out the navigation page.

I wrote about the earliest Justice Society of America comics several months ago and described those 1940s superheroes as colorful blank slates. There are many possible ways to fill in those blanks, and various comic book creators have produced solid stories doing precisely that.

An excellent example is The Golden Age, a 1993 miniseries written by James Robinson and illustrated by Paul Smith. DC published this book under its Elseworlds banner, freeing Robinson and Smith from the normal continuity constraints.

The Golden Age focuses on the end of its titular era, the late 1940s. In the real world, superhero comics entered a period of decline after World War II. Many of those colorful characters faded away as their popularity waned. In this book, the Justice Society and most other masked heroes decide to retire from crimefighting once the war is over. They go their separate ways and try to lead normal lives, with varying degrees of success. All the while, the threat of fascism is rising anew, cloaked in patriotic rhetoric.

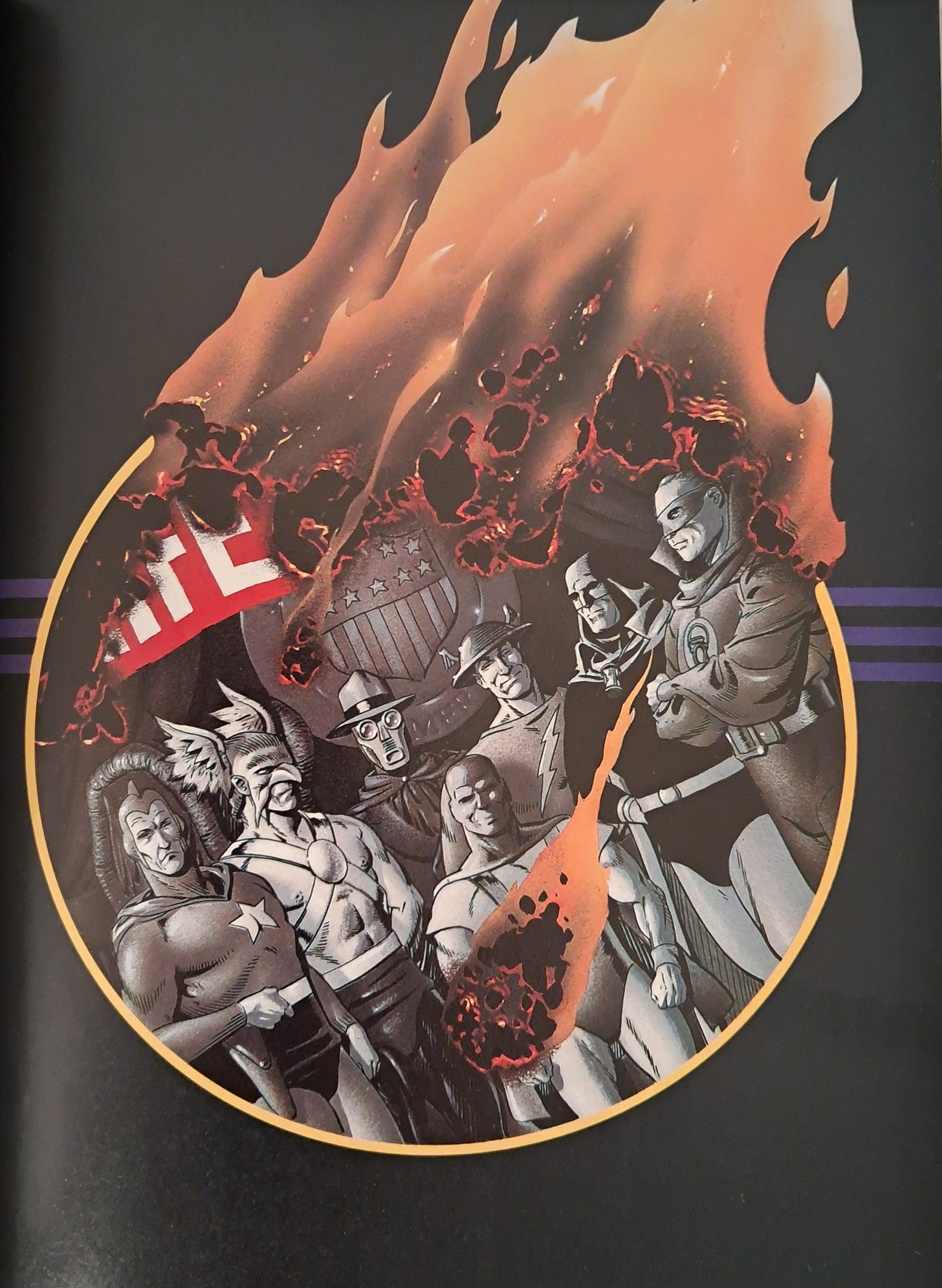

The book juggles a large cast, mixing recognizable characters such as the original Green Lantern and Hawkman with obscure ones such as Captain Triumph and the Tarantula. Prominent roles also go to Johnny Quick, Liberty Belle, Hourman, the original Atom, and Robotman, among others.

One key figure is a forgotten crimefighter whose origins go all the way back to Action Comics #1. Superman’s debut comic also included the debut of Tex Thomson, who in Action Comics #33 would put on a mask and adopt the name Mr. America.

In The Golden Age, Tex (last name spelled as “Thompson” here) receives a hero’s welcome when the public learns that President Roosevelt had tapped him for a top-secret mission. As the Americommando, Tex Thompson infiltrated the upper ranks of the Nazis and took down Hitler’s top men, as well as Hitler himself. Now, Thompson trades on his wartime success to kick off a political career. His speeches take on an aggressively anti-communist bent.

Senator Thompson spearheads a new program of government-backed superheroes with public identities. The new age requires a new type of hero, patriots without masks or secrets who are fully answerable to their country. But, of course, the men claiming to have no secrets are the ones with the most to hide. And Thompson has a rather chilling secret himself.

Various other characters have their own arcs. Alan Scott has given up being the Green Lantern. After the devastation of atomic bombs, he wonders what right he or anyone else has to wield such power. He now focuses on running his radio station and protecting his employees, some of whom are being targeted by the House Un-American Activities Committee.

There’s a great scene in which an old foe strikes, and Alan automatically slips into Green Lantern mode even though he’s wearing a suit and doesn’t have his ring. He doesn’t exactly win the fight, but he proves that Green Lantern was more than just a colorful gimmick. Beneath that emerald aura was a genuine man.

Johnny Chambers, the former Johnny Quick, is compiling a documentary about the glory days of the mystery men. His marriage to Libby Lawrence, the former Liberty Belle, has crumbled, and Johnny consoles himself with work and cigarettes. Libby, meanwhile, is seeing Jonathan Law, formerly the Tarantula and now a struggling writer who resents his girlfriend’s media career.

Ted Knight, the former Starman, now resides in a sanitarium. His research contributed to the development of the atomic bomb, and the guilt has crushed his spirit—during the day, anyway. At night, he acquires a manic, restless energy.

Rex Tyler still clings to his Hourman persona. He’s outright addicted to it. Given the source of his powers—pills that give him super-strength for one hour—it’s the obvious approach, but it fits. The pills are no longer lasting a full hour, so Rex becomes obsessed with creating a better version.

Al Pratt, the original Atom, is also not ready to give up on his glory days. He’s younger than the rest of the Justice Society, after all, so why would he want to retire? Thompson’s program proves to be a seductive opportunity for him.

Paul Kirk, formerly the Manhunter, is being relentlessly pursued by dangerous men, but he can’t even remember why they’re hunting him.

There’s even more than that. The way it weaves together so many different perspectives and plotlines, it’s not hard to imagine this story being reworked into a novel. It wouldn’t be easy to write that novel, but the elements of an excellent novel are present. In any case, it’s already an excellent comic book, which benefits from the exceptional artwork of Paul Smith.

The panels are fluid and demonstrate great range. One scene employs surreal imagery to convey Hourman’s drug-fueled confusion (the excerpt above) while another evokes the rough-hewn purity and innocence of Golden Age comics (below).

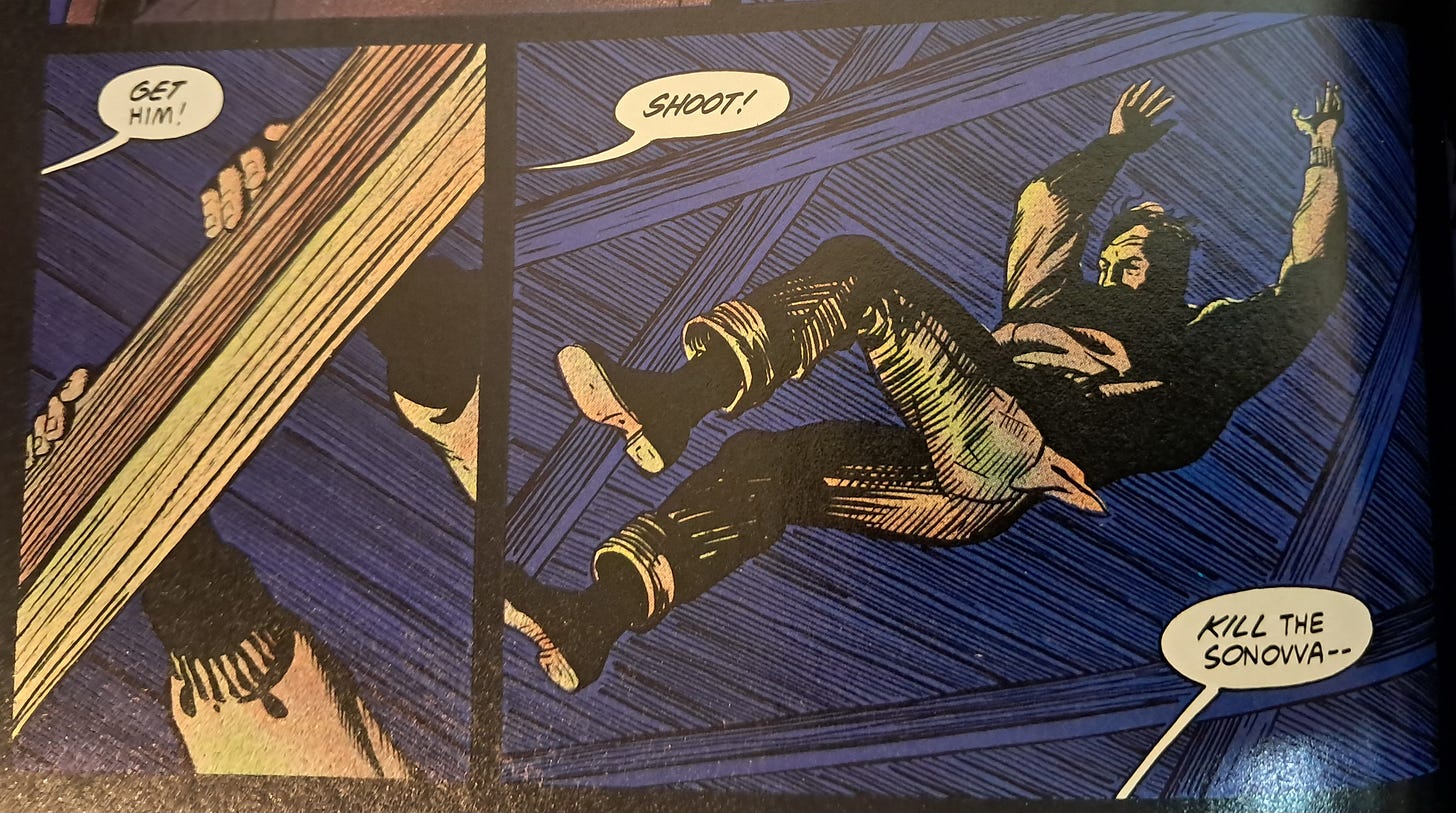

Smith draws expressive faces. His characters can act out their scenes, which is vital to a story that spends much of its time focusing on the people behind the masks. But his action scenes, too, are well choreographed, giving characters specific, meaningful beats to play out.

The Golden Age could come across as a slimmed-down version of Watchmen, but it’s not that. Yes, both examine old-school mystery men through a more adult lens, and Cold War paranoia factors into the plots. But whereas Watchmen deconstructed the genre, The Golden Age also reconstructs it.

The climactic action pulls various superheroes and costumed crimefighters out of their retirements or semi-retirements. They leap into action when the need arises, functioning as individuals while showing little regard for their own individual well-being. It’s sort of like the one last heist trope, except it’s more like one last chance to be superheroes. They step up one more time to oppose a seemingly unstoppable force of pure evil, one who had been hiding in plain sight.

Watchmen had crafted a morally murky situation in which the world’s smartest man engineers the murder of millions to trick everyone into world peace, but The Golden Age works through the darkness and uncertainty to build toward a more heroic, optimistic conclusion.

The story breaks down these classic characters, transforming the colorful blank slates into flawed human beings. But then it builds them back up into heroes, showing how their ideals will always be needed, no matter how times change.

Wow, this sounds like a pretty interesting comic - will have to check it out!

It almost seems like a prelude to what the movie "The Incredibles" would be like- they dealt with similar themes as well as a similar past time period...